AUG. 27, 2015

Consider, if you will, your favorite neurotic. You may need to look no further than across your breakfast table, or conjure a picture of the nation’s neurotic laureate — Woody Allen. Or perhaps you’d reach back in history, say, to Isaac Newton -- father of calculus, discoverer of the universal laws of motion, and a world-class neurotic. Throughout his long life, Newton was angry, secretive, thin-skinned, guilt-ridden and prone to fits of melancholy.

An Opinion piece published Thursday invites you to consider why your favorite neurotic is more likely than his or her sunny opposite to be creative. Writing in the scientific journal Trends in Cognitive Science, a team of neuroscientists proposes that neuroticism — a lifelong inclination toward negative psychological states — may have a silver lining.

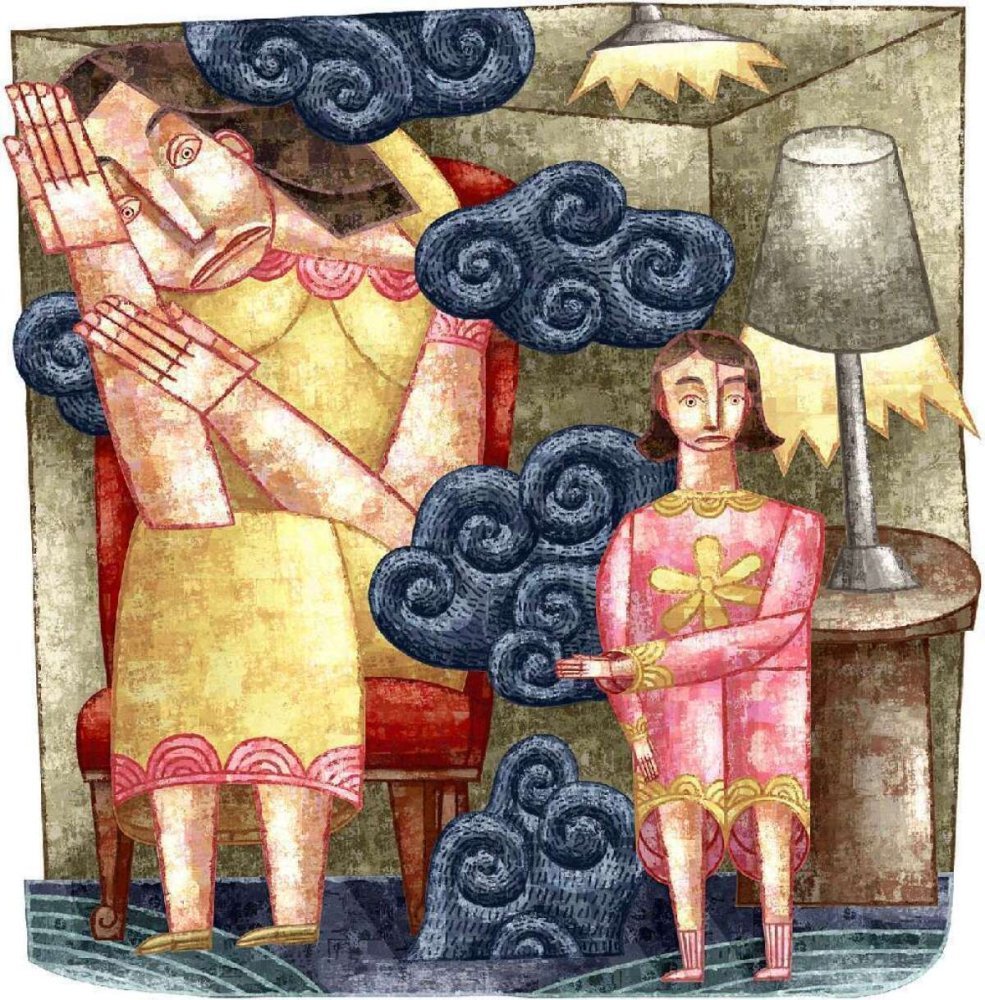

The neurotic, writes a team led by King’s College psychologist Adam M. Perkins, thinks too much. Even in circumstances blissfully free of strife, his or her brain works overtime manufacturing threats, insults and dangers. Where they exist, it embellishes, embroiders and explains them. It is a wellspring of self-generated thought — ponderings wrought, seemingly, of whole cloth.

Some would call it rumination. But the brain built to generate a stream of brooding misery even on the sunniest day may also be a brain primed to see things in ways that don’t conform to everyday realities, write Perkins and his colleagues: A font of creativity, it conjures up threats that don’t exist, and imagines circumstances that might explain the vague sense of fear and unhappiness a neurotic feels.

Those fixed and predictable quirks of the neurotic brain, Perkins and his colleagues posit, may lay the foundation for creative genius. While yet to be shown directly in the lab, they suggest the neural link between neurosis and creativity is strongly suggested by existing research.

Neurosis — one of the “big five” personality traits that reliably characterize individuals’ thought patterns and behavior — is very real (the remaining traits are agreeableness, openness, extraversion and conscientiousness). By a variety of measures, people who score highly for neurotic personality traits are more moody, anxious and irritable than are low scorers. They tend to stay that way throughout life, irrespective of changing circumstances.

Studies have shown that neurotics are highly represented in creative occupations, but are more likely to avoid or wash out of professions that require intense, sustained attention, such as military aviation. And they are more likely to experience depression and other mental illness.

Brain scans show that the regions and networks that process and regulate emotions function differently in people in the grips of negative feeling than in those who feel fine. Those functional differences are particularly evident when scientists look at activity in a network of brain regions collectively known as the default mode network.

Active when a person daydreams, ponders her social relationships or considers his past, a properly functioning default mode network appears to forge a sense of self and helps us create social templates so we can interact with others efficiently. But in depression, its activity can become intrusive and hard to turn off.

Existing research has shown that both creative people and highly neurotic people show similar patterns of activity in the default mode network when faced with a specific cognitive task. Both groups find it hard to shut down the daydreaming — along with coordinated activity in the default mode network -- so that more purposeful mental activity can proceed.

In the creative and the neurotic alike, that persistent spontaneous thought generator might be reimagining available information in some new form, or casting an imagined threat in a new role. Nightmare sufferers, who tend to rank high in neuroses, may see that process invade their sleep, the authors wrote.

“I keep the subject constantly before me, and wait ‘til the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light,” Newton wrote to explain his process of intellectual discovery.

In 1687, Newton wrote his opus “Principia Mathematica,” in which he postulated the three universal laws of motion and laid the foundation for classical mechanics. He gained international recognition for his work, which remains a cornerstone of modern science. But he brooded over past mistakes and worried obsessively about whether he, rather than Gottfried Leibniz, would get credit for having developed calculus. In 1693, he suffered a nervous breakdown.

With the relentless rise of the happiness movement, neurotics have developed a bad rap in recent years. While neurosis is, by definition, a fixed and stable personality trait, many have recommended such measures as mindfulness meditation practice to nudge neurotics toward more positive thinking. Antidepressants, a 2009 study found, might do the same.

Efforts to nudge neurotics down the scale might help them feel better and protect them from depression, wrote Perkins and his colleagues. But they might also “do more harm than good,” they cautioned, draining from some natural curmudgeons the creativity that may predispose them to genius.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.