From MedscapeCME Psychiatry & Mental Health

Why Now? Factors That Delay ADHD Diagnosis in Adults CME

Joel L. Young, MD

Parents of children recently diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often ask whether they could have the same problem, having exhibited similar symptoms all their lives. This scenario, the diagnosis of their children leading these adults to an "Aha!" moment, is the most common reason for a first-time diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood.[1] In retrospect they wonder if ADHD could explain their lifelong difficulties with impulsivity, disorganization, procrastination, and the other hallmark features of ADHD.

Despite the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) requirement that adults must have exhibited ADHD symptoms at age 7 or before to be diagnosed with ADHD,[2] many people are not diagnosed with ADHD until adulthood, and only retrospective information from the patients themselves or their parents offers any clues to the existence of early symptoms.

Inevitably, patients and clinicians ask a standard question. Why now? Why do some adults never diagnosed with ADHD in childhood receive this diagnosis as adults? How did they make it well into adulthood without detection and, once treated, why does treatment seem so necessary for continued well-being? This column offers explanations for a belated diagnosis, including likely reasons why the parents of today's adults failed to make the ADHD connection in the past, as well as other reasons. These reasons may include formerly effective adaptive mechanisms that fail in a new situation, new demands intruding on a career that had been forgiving of ADHD symptoms, high intelligence and compensating mechanisms that mask ADHD until coping techniques fail with the demands of college, and missed diagnosis related to gender-specific factors and symptoms.

ADHD: Unknown, Feared, and Misunderstood in Past Years

The parents of today's adults were often unaware, skeptical, or even afraid of an ADHD diagnosis. To understand why, a little history is in order. In the 1950s, the terminology for what is now known as ADHD was "hyperkinetic impulse disorder." A decade later, "minimal brain dysfunction" came into vogue, a term reflecting underlying neurologic pathology.[3] Yet families of that time often and understandably viewed such descriptions as pejorative; the nomenclature connoted brain damage and/or impaired intelligence, and many parents resisted acknowledging that their child could have such a disorder.

In addition, psychiatrists in past eras often looked askance at what is now called ADHD. Psychodynamic and psychoanalytic models were in ascendancy, and despite the introduction of antipsychotic drugs and lithium for adults with severe mental illness, the basic tenets of biologic psychiatry were not well-integrated into American society or among psychiatrists.

Furthermore, symptoms of inattention and distractibility were not understood to be medication-responsive and children with these ADHD characteristics were not identified.

Another key reason why ADHD was not identified in childhood among many of today's adults with ADHD was that some very prominent popular publications warned of the pernicious effects of psychiatric medication; for example, Mayes and colleagues[3] identify an influential Washington Post article in 1970 that estimated that 5%-10% of Omaha school children were dosed with behavior-controlling medications, with or without parental permission. In actuality, the medicated students were children with special needs and they were not forced into treatment. Nevertheless, people at that time often believed that what they had read must be true, and thus, parents were daunted. But they were not the only ones who believed the scary drug stories. The media hype also generated enormous concern in Washington over possible drug misuse and abuse. National conferences and congressional hearings were organized. In 1971, Congress ordered the Drug Enforcement Administration to categorize amphetamines and methylphenidate as Schedule II drugs.[3] This action limited access to stimulants and placed them out of reach of children without resources or motivated parents. As a result, today's adult came of age in a climate that was indifferent and sometimes actively hostile to the legitimacy of ADHD.

Adaptive Behaviors: How They May Delay Diagnosis

ADHD symptoms are evident early in life and clearly affect personality development.[4] These personality features run the gamut of adaptability. Hyperactivity and impulsivity may lead to antisocial behaviors and decidedly negative outcomes.

By contrast, certain individuals with ADHD may reject the inherent entropy of their condition and respond by developing obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) traits.[5] On some level, they innately recognize that their natural tendency is to remain disorganized and tardy, so they force themselves to stay rigidly rule bound. They develop lists and then lists of lists as reminders. They check and recheck where they place their keys and cell phone, for example, even to the point of developing rituals. (The keys must always be in the jacket pocket, the cell phone must be placed on a table by the front door when arriving home, and so forth.) They establish strict daily schedules, and avoid any deviations from the routine out of fear that 1 misstep could hopelessly unravel their plans for the entire day or even the week. In social conversations, such individuals can become overly verbose, driven by a sensation that unless they explain every minute detail, their message will not be understood.[5]

As with many behavioral adaptations, success may be situation-specific. The person with ADHD who has OCPD traits can do well during some periods of life and considerably less well at other times. For example, once the individual transitions to a less controlled environment, ie, from a parochial school to a public high school or from homemaker to having a job in the workplace, his or her formerly adaptive behaviors, such as the need to maintain strict routines, may appear maladaptive to others and may not be tolerated. During these transitions, individuals with OCPD traits encounter the difficulties that finally force them into a therapeutic setting where longstanding ADHD is identified and the reason for the delayed diagnosis is understood.

Other adaptive features of the undiagnosed patient with ADHD are also frequently seen in the clinic. Individuals who are caffeine-dependent may inadvertently be self-medicating ADHD.[6] An abrupt discontinuation of this "over-the-counter stimulant" deprives them of an ad hoc treatment and symptoms once partially treated with caffeine will now surface.

In a similar manner, adults with ADHD often incorporate demanding physical exercise into their daily routines.[7] Over time, an injury or normal aging obviates intense exercise and the physiologic benefit of physical exertion that previously mitigated inherent ADHD deficits is lost. For this reason, a caffeine and exercise history, including disruptions in intake or routine, should be obtained from patients who present in adulthood with possible ADHD symptoms.

Career Choices and Changes

ADHD is a disorder of paradoxes; some individuals have delayed diagnoses because of OCPD tendencies; others, particularly those with hyperactivity and impulsivity, may succeed in a career that satiates their need for novelty or physical activity. Such a person may migrate to fire-fighting, race car driving, or working in an emergency department.[8]

Edward's case exemplifies this finding. As an ombudsman for a manufacturing company, Edward traveled constantly to address urgent problems at factories throughout the world. Gregarious and resourceful, he was well-received and earned excellent performance evaluations. His administrative assistant completed the required paperwork, sparing him inconvenient details and allowing him to react quickly to novel challenges. Because of his success in the field, Edward was reassigned to a supervisory job at the home office. In this setting, he was asked to manage others in a corporate structure that valued a strict chain of command, and a careful accounting of work hours, regular submission of expense forms, and timely written reports. All these changes occurred just as Edward's support staff dwindled. Edward's new supervisor was aghast by what he perceived as Edward's blatant disregard for standard procedure, and Edward's job evaluations soon deteriorated. Edward became intensely preoccupied with how he was viewed by others, and this persistent anxiety prompted him to seek psychiatric help.

After some time, Edward's therapist identified his ADHD, and discerned Edward's method of adaptation. Despite effective treatment, Edward's fate at work was sealed by this time and he was terminated from his job. Only when he found another nonmanagerial, unsupervised job, this time in international sales, was he able to resurrect and even exceed his previous level of mastery and self-esteem.

High Intelligence May Partially Compensate for ADHD Deficits -- Until College

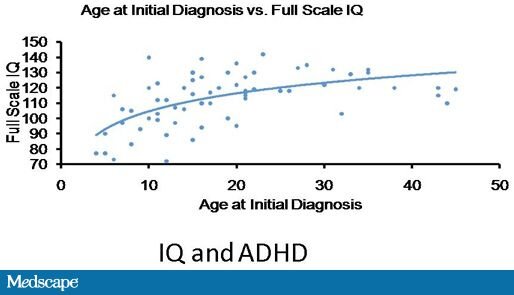

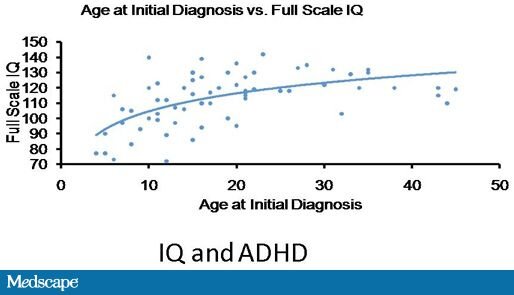

Adults with high IQs may be able to compensate for ADHD deficits and forestall the diagnosis. As Horrigan and colleagues[9] demonstrated, there is often an inverse relationship between intelligence and the age of diagnosis with ADHD; ie, the brighter the individual, the more delayed the diagnosis (Figure).

Figure. High IQ can compensate for the impairments of ADHD, and forestall diagnosis of ADHD. Adapted from Horrigan J. 47th Annual AACAP Meeting; October 24-29, 2000; New York, NY.

Not uncommonly, the diagnosis of ADHD is not identified until college years. A student's high IQ combined with good or adequate high school grades prove sufficient to gain admission into college. Sometimes these good grades were the result of hard work; in the case of noncompetitive high schools, however, high marks can result from even minimal work. The students' families may have prodded them to wake up, complete their homework, and meet other crucial deadlines. Once at college, however, the lack of structure in daily life, numerous social distractions, and the enhanced course demands and complexity of the courses proves overwhelming to students with undiagnosed ADHD.

These clinical scenarios are repeated yearly in college counseling offices. Even selective institutions need to intervene and offer ADHD treatment. By allowing the individual to focus on productive endeavors, medications can liberate the gifted student from academic frustration.[10]

Gender Issues: Women and ADHD

Individuals with the predominantly inattentive type ADHD are at risk for a delayed diagnosis of ADHD, with a higher prevalence of women than men in this subtype. Inattentive symptoms impair scholastic functioning but unlike the predominantly hyperactive and impulsive type of ADHD, inattentive girls rarely exhibit behaviors that negatively affect others; daydreaming or inattention does not bother others compared with the excessive movements and overt actions of the hyperactive child with ADHD.[11,12]

Yet, relative to their potential, these girls are underperforming. Only recently have inattention and distractibility been identified as treatable symptoms; in the past, daydreaming, carelessness, and disorganization were misattributed to the strains of adolescence, female hormones, or societal norms dissociated from ADHD itself.[5] As a result, schools have generally targeted their available resources to other obviously struggling students. This lack of understanding has led teachers and parents to blame the girl herself, encouraging her to try harder, focus more intensely, and concentrate more. In short, many girls who are now women were asked to "will away" the very deficits that defined their ADHD. Many of them did "try" and failed, subsequently blaming themselves.

Chronic underperformance has profound consequences on life decisions. Adolescents who perform poorly in school because of untreated ADHD may forego further schooling, even when they are bright. Without the positive reinforcement that comes with scholastic success, adolescents strive to distinguish themselves in some other manner, be it athletically or creatively. Sometimes failure drives girls (and boys) into social alienation and the consequent decisions to ally themselves with troubled friends and engage in maladaptive behaviors. Impaired self-esteem and a troubled adolescence may be the prelude to difficulties in young adulthood.

Years later what finally brings such a woman into the doctor's office to obtain a long delayed diagnosis of ADHD? In some instances, she may pursue psychiatric counseling to explore the conflicts of her youth. Alternatively, she might have an epiphany when her children encounter difficulties similar to her own and they are diagnosed with the condition. Lastly her doctor might reexamine her diagnosis after she has experienced an inadequate response to antidepressant and anti-anxiety treatment.[5]

A Missed or Wrong Diagnosis

An inaccurate diagnosis remains a common reason for a delayed diagnosis of ADHD and this problem usually results from incomplete diagnostic formulations. Often, depressed mood becomes the focus of treatment, usually to the exclusion of ADHD.[13] The phenomenon of patients with ADHD receiving a diagnosis of depression is both understandable and unfortunate. Patients with untreated ADHD become frustrated with their symptoms. They are angry at themselves and irritated by their pervasive procrastination and chronic disorganization. Their employers abhor their tardiness and after repeated episodes of overdrafting bank accounts or impulsive overspending, their spouses regard them as irresponsible. Psychiatrists may misinterpret this frustration as depression, and antidepressant medications may be prescribed reflexively. Of course, sometimes depression is present, along with ADHD, and the depression is identified while the ADHD remains undiagnosed.

Yet frustration is not always related to major depression, and if the individual's issues primarily stem from ADHD rather than depression, then conventional antidepressant treatment will be ineffective.[5] Ideally, a failed trial of an adequate dose of antidepressants should alert the clinician to reexamine the underlying diagnosis; however, in standard practice, many clinicians move from 1 antidepressant to another, perhaps switching from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor to a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or adding bupropion or a low-dose atypical antipsychotic to the antidepressant. Unfortunately, the most commonly referenced study regarding strategies to address treatment-resistant depression does not emphasize the necessity of an accurate diagnosis.[14] In this algorithm, the use of stimulants in tandem with antidepressants receives little notice.[14]

Adults with ADHD may be misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder. Although mood lability is not part of the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, the reality is that patients with undiagnosed ADHD may overreact to simple stimuli and demonstrate mood inconsistency. This characteristic can be amplified in the treated state as well; mood swings may occur as the stimulant level wanes.[15] This end-of-dose effect might be misidentified as a bipolar disorder and inaccurate treatment can occur for years.

Atmaca and colleagues[16] describe a patient with mood swings that were initially diagnosed as bipolar disorder. The authors detail a 6-year history of multiple psychotropic treatment failures, including an unproductive psychiatric hospitalization. In the end, the patient consulted another psychiatrist, was diagnosed with ADHD, treated with stimulants, and dramatically improved.[16]

ADHD can mimic other conditions. Comprehensive screening of all patients who present in psychological distress necessitates an assessment for anxiety, depression, mania, substance use disorder, and also ADHD. Developing and then confirming a differential diagnosis reduces the likelihood of overlooking this highly prevalent and debilitating disorder, and treating a patient unproductively. Screening tools for ADHD can achieve this goal.[17]

Raw data from a recent, not yet published survey of adults treated for ADHD show that 59% reported a 2-week period of depressed mood. Nearly half of those surveyed reported panic attacks, and 60% endorsed generalized anxiety (Young JL, Saal J. A survey of outpatient adults with ADHD. 2009. Unpublished raw data).

ADHD is a disorder that originates in childhood and thus always predates the onset of anxiety and mood disorders. When these conditions do co-occur in adults, ADHD is often not identified.[18] Existing data on the treatment of comorbid conditions is limited; a study of young patients with both ADHD and generalized anxiety revealed that atomoxetine improved both symptom complexes.[19] Only a few trials have examined comorbid ADHD and depression but combining selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and stimulants is a common practice.[20]

The Importance of Diagnosis and Treatment: Future Goals

ADHD is a common disorder, affecting an estimated 3%-7% of school-age American children[21] and 4.4%[18] of American adults. Throughout the course of their lives, undiagnosed individuals with ADHD pay a huge cost. Compared with normal controls, they have a lower educational outcome, lower lifetime earning potential, and higher rates of divorce. In general, adults with ADHD have higher rates of psychiatric illness and substance abuse and are significantly more likely to encounter the criminal justice system.[1] These incontrovertible data should be of utmost concern to psychiatrists.

Schools and healthcare providers should screen for ADHD as they do for deafness and visual acuity. Currently, many adults with ADHD obtain their diagnosis only after they see how their child's struggles with impulsivity, disorganization, procrastination, and other hallmark features of ADHD mirror their own history. To reduce the frequency of delayed diagnosis, a reasonable goal for the next decade would be to upgrade ADHD from a diagnosis of exclusion or suggestion to one that doctors proactively consider in their evaluation of psychiatrically distressed patients.

Conclusion

Many individuals with ADHD are not diagnosed for the first time until adulthood, although their symptoms have been present, in some form or another, since childhood. Several possible factors may explain a belated diagnosis. Given the relatively recent awareness that ADHD exists in adults, the person's parents may have lacked the knowledge or failed to acknowledge the adult's childhood symptoms. Patients with high IQs may have once been able to compensate for their symptoms but find that these coping mechanisms have ceased to work in a more complex adult world. They may have held a job that was forgiving of or masked their ADHD symptoms but a promotion or job change has caused the symptoms to loom large. The adult or their treating clinicians may have attributed their symptoms to another diagnosis. Or perhaps their diagnosis is of the inattentive type and was overlooked due to the often unobservable nature of these symptoms (a common trajectory among women with ADHD). Often, the diagnosis of their own child is the impetus for the adult to seek a diagnosis. Regardless of the catalyst, accurate diagnosis will likely result in much-needed help and a vastly improved quality of life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

1.No author attributed. 2001. ADHD in adulthood. Available online at: http://www.hms.harvard.edu/hmni/On_The_Brain/Volume08/OTB_Vol8No2_SpringSummer2001.pdf Accessed October 15, 2009.

2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Text revision, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

3.Mayes R, Rafalovich A. Suffer the restless children: the evolution of ADHD and paediatric stimulant use. Hist Psychiatry. 2007;18:435-457. Abstract

4.Nigg JT, John OP, Blaskey LG, et al. Big five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:451-469. Abstract

5.Young J. ADHD Grown Up: A Guide to Adolescent and Adult ADHD. New York: WW Norton; 2007.

6.Broderick P, Benjamin AB. Caffeine and psychiatric symptoms: a review. J Oklahoma State Med Assoc. 2004;97:538-542.

7.Azrin NH, Ehle CT, Beaumont, AL. Physical exercise as a reinforcer to promote calmness of an ADHD child. Behav Mod. 2006;30:564-570.

8.Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders CNS Spectrum. 2008;13:977-984.

9.Horrigan JP, Kohli RR. The impact of IQ on the timely diagnosis of ADHD. Poster and abstracts of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47th Annual Meeting; October 24-29, 2000; New York, NY.

10.Okie S. ADHD in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;25:2637-2641.

11.Solden S. Women with Attention Deficit Disorder. Grass Valley, Calif: Underwood Books; 1995.

12.Nadeau K, Quinn P. The history of ADHD -- an unexamined gender bias. In: Quinn PO, Nadeau KG, eds. Gender Issues and ADHD: Research, Diagnosis and Treatment. Silver Spring, Md: Advantage Books; 2002:2-22.

13.Kelly J. Depression often misdiagnosed in primary care. Available at: /viewarticle/706714 Accessed December 7, 2009.

14.Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a Star*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905-1917. Abstract

15.McIntyre R. Bipolar disorder and ADHD: clinical concerns. CNS Spectr. 2009;14:8-9.

16.Atmaca M, Ozler S, Topuz M, Goldstein S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder erroneously diagnosed and treated as bipolar disorder. J Atten Disord. 2009;13:197-198. Abstract

17.Young J. Women with ADHD: unique presentations and treatment approaches. Available at: http://cme.medscape.com/viewarticle/711520_print Accessed December 7, 2009.

18.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006:163:716-723. Abstract

19.Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, et al. Atomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder. J Am Adolesc Psychiatry Acad Child. 2007;46:1119-1127.

20.Young J. Oros-methylphenidate added to fluoxetine in treatment-resistant depression. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association's 58th Institute on Psychiatric Services, October 2006; New York, NY.

21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ADHD Data & Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncgbddd/adhd/data.html Accessed November 8, 2009.

Why Now? Factors That Delay ADHD Diagnosis in Adults CME

Joel L. Young, MD

Parents of children recently diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often ask whether they could have the same problem, having exhibited similar symptoms all their lives. This scenario, the diagnosis of their children leading these adults to an "Aha!" moment, is the most common reason for a first-time diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood.[1] In retrospect they wonder if ADHD could explain their lifelong difficulties with impulsivity, disorganization, procrastination, and the other hallmark features of ADHD.

Despite the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) requirement that adults must have exhibited ADHD symptoms at age 7 or before to be diagnosed with ADHD,[2] many people are not diagnosed with ADHD until adulthood, and only retrospective information from the patients themselves or their parents offers any clues to the existence of early symptoms.

Inevitably, patients and clinicians ask a standard question. Why now? Why do some adults never diagnosed with ADHD in childhood receive this diagnosis as adults? How did they make it well into adulthood without detection and, once treated, why does treatment seem so necessary for continued well-being? This column offers explanations for a belated diagnosis, including likely reasons why the parents of today's adults failed to make the ADHD connection in the past, as well as other reasons. These reasons may include formerly effective adaptive mechanisms that fail in a new situation, new demands intruding on a career that had been forgiving of ADHD symptoms, high intelligence and compensating mechanisms that mask ADHD until coping techniques fail with the demands of college, and missed diagnosis related to gender-specific factors and symptoms.

ADHD: Unknown, Feared, and Misunderstood in Past Years

The parents of today's adults were often unaware, skeptical, or even afraid of an ADHD diagnosis. To understand why, a little history is in order. In the 1950s, the terminology for what is now known as ADHD was "hyperkinetic impulse disorder." A decade later, "minimal brain dysfunction" came into vogue, a term reflecting underlying neurologic pathology.[3] Yet families of that time often and understandably viewed such descriptions as pejorative; the nomenclature connoted brain damage and/or impaired intelligence, and many parents resisted acknowledging that their child could have such a disorder.

In addition, psychiatrists in past eras often looked askance at what is now called ADHD. Psychodynamic and psychoanalytic models were in ascendancy, and despite the introduction of antipsychotic drugs and lithium for adults with severe mental illness, the basic tenets of biologic psychiatry were not well-integrated into American society or among psychiatrists.

Furthermore, symptoms of inattention and distractibility were not understood to be medication-responsive and children with these ADHD characteristics were not identified.

Another key reason why ADHD was not identified in childhood among many of today's adults with ADHD was that some very prominent popular publications warned of the pernicious effects of psychiatric medication; for example, Mayes and colleagues[3] identify an influential Washington Post article in 1970 that estimated that 5%-10% of Omaha school children were dosed with behavior-controlling medications, with or without parental permission. In actuality, the medicated students were children with special needs and they were not forced into treatment. Nevertheless, people at that time often believed that what they had read must be true, and thus, parents were daunted. But they were not the only ones who believed the scary drug stories. The media hype also generated enormous concern in Washington over possible drug misuse and abuse. National conferences and congressional hearings were organized. In 1971, Congress ordered the Drug Enforcement Administration to categorize amphetamines and methylphenidate as Schedule II drugs.[3] This action limited access to stimulants and placed them out of reach of children without resources or motivated parents. As a result, today's adult came of age in a climate that was indifferent and sometimes actively hostile to the legitimacy of ADHD.

Adaptive Behaviors: How They May Delay Diagnosis

ADHD symptoms are evident early in life and clearly affect personality development.[4] These personality features run the gamut of adaptability. Hyperactivity and impulsivity may lead to antisocial behaviors and decidedly negative outcomes.

By contrast, certain individuals with ADHD may reject the inherent entropy of their condition and respond by developing obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) traits.[5] On some level, they innately recognize that their natural tendency is to remain disorganized and tardy, so they force themselves to stay rigidly rule bound. They develop lists and then lists of lists as reminders. They check and recheck where they place their keys and cell phone, for example, even to the point of developing rituals. (The keys must always be in the jacket pocket, the cell phone must be placed on a table by the front door when arriving home, and so forth.) They establish strict daily schedules, and avoid any deviations from the routine out of fear that 1 misstep could hopelessly unravel their plans for the entire day or even the week. In social conversations, such individuals can become overly verbose, driven by a sensation that unless they explain every minute detail, their message will not be understood.[5]

As with many behavioral adaptations, success may be situation-specific. The person with ADHD who has OCPD traits can do well during some periods of life and considerably less well at other times. For example, once the individual transitions to a less controlled environment, ie, from a parochial school to a public high school or from homemaker to having a job in the workplace, his or her formerly adaptive behaviors, such as the need to maintain strict routines, may appear maladaptive to others and may not be tolerated. During these transitions, individuals with OCPD traits encounter the difficulties that finally force them into a therapeutic setting where longstanding ADHD is identified and the reason for the delayed diagnosis is understood.

Other adaptive features of the undiagnosed patient with ADHD are also frequently seen in the clinic. Individuals who are caffeine-dependent may inadvertently be self-medicating ADHD.[6] An abrupt discontinuation of this "over-the-counter stimulant" deprives them of an ad hoc treatment and symptoms once partially treated with caffeine will now surface.

In a similar manner, adults with ADHD often incorporate demanding physical exercise into their daily routines.[7] Over time, an injury or normal aging obviates intense exercise and the physiologic benefit of physical exertion that previously mitigated inherent ADHD deficits is lost. For this reason, a caffeine and exercise history, including disruptions in intake or routine, should be obtained from patients who present in adulthood with possible ADHD symptoms.

Career Choices and Changes

ADHD is a disorder of paradoxes; some individuals have delayed diagnoses because of OCPD tendencies; others, particularly those with hyperactivity and impulsivity, may succeed in a career that satiates their need for novelty or physical activity. Such a person may migrate to fire-fighting, race car driving, or working in an emergency department.[8]

Edward's case exemplifies this finding. As an ombudsman for a manufacturing company, Edward traveled constantly to address urgent problems at factories throughout the world. Gregarious and resourceful, he was well-received and earned excellent performance evaluations. His administrative assistant completed the required paperwork, sparing him inconvenient details and allowing him to react quickly to novel challenges. Because of his success in the field, Edward was reassigned to a supervisory job at the home office. In this setting, he was asked to manage others in a corporate structure that valued a strict chain of command, and a careful accounting of work hours, regular submission of expense forms, and timely written reports. All these changes occurred just as Edward's support staff dwindled. Edward's new supervisor was aghast by what he perceived as Edward's blatant disregard for standard procedure, and Edward's job evaluations soon deteriorated. Edward became intensely preoccupied with how he was viewed by others, and this persistent anxiety prompted him to seek psychiatric help.

After some time, Edward's therapist identified his ADHD, and discerned Edward's method of adaptation. Despite effective treatment, Edward's fate at work was sealed by this time and he was terminated from his job. Only when he found another nonmanagerial, unsupervised job, this time in international sales, was he able to resurrect and even exceed his previous level of mastery and self-esteem.

High Intelligence May Partially Compensate for ADHD Deficits -- Until College

Adults with high IQs may be able to compensate for ADHD deficits and forestall the diagnosis. As Horrigan and colleagues[9] demonstrated, there is often an inverse relationship between intelligence and the age of diagnosis with ADHD; ie, the brighter the individual, the more delayed the diagnosis (Figure).

Figure. High IQ can compensate for the impairments of ADHD, and forestall diagnosis of ADHD. Adapted from Horrigan J. 47th Annual AACAP Meeting; October 24-29, 2000; New York, NY.

Not uncommonly, the diagnosis of ADHD is not identified until college years. A student's high IQ combined with good or adequate high school grades prove sufficient to gain admission into college. Sometimes these good grades were the result of hard work; in the case of noncompetitive high schools, however, high marks can result from even minimal work. The students' families may have prodded them to wake up, complete their homework, and meet other crucial deadlines. Once at college, however, the lack of structure in daily life, numerous social distractions, and the enhanced course demands and complexity of the courses proves overwhelming to students with undiagnosed ADHD.

These clinical scenarios are repeated yearly in college counseling offices. Even selective institutions need to intervene and offer ADHD treatment. By allowing the individual to focus on productive endeavors, medications can liberate the gifted student from academic frustration.[10]

Gender Issues: Women and ADHD

Individuals with the predominantly inattentive type ADHD are at risk for a delayed diagnosis of ADHD, with a higher prevalence of women than men in this subtype. Inattentive symptoms impair scholastic functioning but unlike the predominantly hyperactive and impulsive type of ADHD, inattentive girls rarely exhibit behaviors that negatively affect others; daydreaming or inattention does not bother others compared with the excessive movements and overt actions of the hyperactive child with ADHD.[11,12]

Yet, relative to their potential, these girls are underperforming. Only recently have inattention and distractibility been identified as treatable symptoms; in the past, daydreaming, carelessness, and disorganization were misattributed to the strains of adolescence, female hormones, or societal norms dissociated from ADHD itself.[5] As a result, schools have generally targeted their available resources to other obviously struggling students. This lack of understanding has led teachers and parents to blame the girl herself, encouraging her to try harder, focus more intensely, and concentrate more. In short, many girls who are now women were asked to "will away" the very deficits that defined their ADHD. Many of them did "try" and failed, subsequently blaming themselves.

Chronic underperformance has profound consequences on life decisions. Adolescents who perform poorly in school because of untreated ADHD may forego further schooling, even when they are bright. Without the positive reinforcement that comes with scholastic success, adolescents strive to distinguish themselves in some other manner, be it athletically or creatively. Sometimes failure drives girls (and boys) into social alienation and the consequent decisions to ally themselves with troubled friends and engage in maladaptive behaviors. Impaired self-esteem and a troubled adolescence may be the prelude to difficulties in young adulthood.

Years later what finally brings such a woman into the doctor's office to obtain a long delayed diagnosis of ADHD? In some instances, she may pursue psychiatric counseling to explore the conflicts of her youth. Alternatively, she might have an epiphany when her children encounter difficulties similar to her own and they are diagnosed with the condition. Lastly her doctor might reexamine her diagnosis after she has experienced an inadequate response to antidepressant and anti-anxiety treatment.[5]

A Missed or Wrong Diagnosis

An inaccurate diagnosis remains a common reason for a delayed diagnosis of ADHD and this problem usually results from incomplete diagnostic formulations. Often, depressed mood becomes the focus of treatment, usually to the exclusion of ADHD.[13] The phenomenon of patients with ADHD receiving a diagnosis of depression is both understandable and unfortunate. Patients with untreated ADHD become frustrated with their symptoms. They are angry at themselves and irritated by their pervasive procrastination and chronic disorganization. Their employers abhor their tardiness and after repeated episodes of overdrafting bank accounts or impulsive overspending, their spouses regard them as irresponsible. Psychiatrists may misinterpret this frustration as depression, and antidepressant medications may be prescribed reflexively. Of course, sometimes depression is present, along with ADHD, and the depression is identified while the ADHD remains undiagnosed.

Yet frustration is not always related to major depression, and if the individual's issues primarily stem from ADHD rather than depression, then conventional antidepressant treatment will be ineffective.[5] Ideally, a failed trial of an adequate dose of antidepressants should alert the clinician to reexamine the underlying diagnosis; however, in standard practice, many clinicians move from 1 antidepressant to another, perhaps switching from a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor to a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or adding bupropion or a low-dose atypical antipsychotic to the antidepressant. Unfortunately, the most commonly referenced study regarding strategies to address treatment-resistant depression does not emphasize the necessity of an accurate diagnosis.[14] In this algorithm, the use of stimulants in tandem with antidepressants receives little notice.[14]

Adults with ADHD may be misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder. Although mood lability is not part of the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, the reality is that patients with undiagnosed ADHD may overreact to simple stimuli and demonstrate mood inconsistency. This characteristic can be amplified in the treated state as well; mood swings may occur as the stimulant level wanes.[15] This end-of-dose effect might be misidentified as a bipolar disorder and inaccurate treatment can occur for years.

Atmaca and colleagues[16] describe a patient with mood swings that were initially diagnosed as bipolar disorder. The authors detail a 6-year history of multiple psychotropic treatment failures, including an unproductive psychiatric hospitalization. In the end, the patient consulted another psychiatrist, was diagnosed with ADHD, treated with stimulants, and dramatically improved.[16]

ADHD can mimic other conditions. Comprehensive screening of all patients who present in psychological distress necessitates an assessment for anxiety, depression, mania, substance use disorder, and also ADHD. Developing and then confirming a differential diagnosis reduces the likelihood of overlooking this highly prevalent and debilitating disorder, and treating a patient unproductively. Screening tools for ADHD can achieve this goal.[17]

Raw data from a recent, not yet published survey of adults treated for ADHD show that 59% reported a 2-week period of depressed mood. Nearly half of those surveyed reported panic attacks, and 60% endorsed generalized anxiety (Young JL, Saal J. A survey of outpatient adults with ADHD. 2009. Unpublished raw data).

ADHD is a disorder that originates in childhood and thus always predates the onset of anxiety and mood disorders. When these conditions do co-occur in adults, ADHD is often not identified.[18] Existing data on the treatment of comorbid conditions is limited; a study of young patients with both ADHD and generalized anxiety revealed that atomoxetine improved both symptom complexes.[19] Only a few trials have examined comorbid ADHD and depression but combining selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and stimulants is a common practice.[20]

The Importance of Diagnosis and Treatment: Future Goals

ADHD is a common disorder, affecting an estimated 3%-7% of school-age American children[21] and 4.4%[18] of American adults. Throughout the course of their lives, undiagnosed individuals with ADHD pay a huge cost. Compared with normal controls, they have a lower educational outcome, lower lifetime earning potential, and higher rates of divorce. In general, adults with ADHD have higher rates of psychiatric illness and substance abuse and are significantly more likely to encounter the criminal justice system.[1] These incontrovertible data should be of utmost concern to psychiatrists.

Schools and healthcare providers should screen for ADHD as they do for deafness and visual acuity. Currently, many adults with ADHD obtain their diagnosis only after they see how their child's struggles with impulsivity, disorganization, procrastination, and other hallmark features of ADHD mirror their own history. To reduce the frequency of delayed diagnosis, a reasonable goal for the next decade would be to upgrade ADHD from a diagnosis of exclusion or suggestion to one that doctors proactively consider in their evaluation of psychiatrically distressed patients.

Conclusion

Many individuals with ADHD are not diagnosed for the first time until adulthood, although their symptoms have been present, in some form or another, since childhood. Several possible factors may explain a belated diagnosis. Given the relatively recent awareness that ADHD exists in adults, the person's parents may have lacked the knowledge or failed to acknowledge the adult's childhood symptoms. Patients with high IQs may have once been able to compensate for their symptoms but find that these coping mechanisms have ceased to work in a more complex adult world. They may have held a job that was forgiving of or masked their ADHD symptoms but a promotion or job change has caused the symptoms to loom large. The adult or their treating clinicians may have attributed their symptoms to another diagnosis. Or perhaps their diagnosis is of the inattentive type and was overlooked due to the often unobservable nature of these symptoms (a common trajectory among women with ADHD). Often, the diagnosis of their own child is the impetus for the adult to seek a diagnosis. Regardless of the catalyst, accurate diagnosis will likely result in much-needed help and a vastly improved quality of life.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

1.No author attributed. 2001. ADHD in adulthood. Available online at: http://www.hms.harvard.edu/hmni/On_The_Brain/Volume08/OTB_Vol8No2_SpringSummer2001.pdf Accessed October 15, 2009.

2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Text revision, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

3.Mayes R, Rafalovich A. Suffer the restless children: the evolution of ADHD and paediatric stimulant use. Hist Psychiatry. 2007;18:435-457. Abstract

4.Nigg JT, John OP, Blaskey LG, et al. Big five dimensions and ADHD symptoms: links between personality traits and clinical symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:451-469. Abstract

5.Young J. ADHD Grown Up: A Guide to Adolescent and Adult ADHD. New York: WW Norton; 2007.

6.Broderick P, Benjamin AB. Caffeine and psychiatric symptoms: a review. J Oklahoma State Med Assoc. 2004;97:538-542.

7.Azrin NH, Ehle CT, Beaumont, AL. Physical exercise as a reinforcer to promote calmness of an ADHD child. Behav Mod. 2006;30:564-570.

8.Barkley RA, Brown TE. Unrecognized attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults presenting with other psychiatric disorders CNS Spectrum. 2008;13:977-984.

9.Horrigan JP, Kohli RR. The impact of IQ on the timely diagnosis of ADHD. Poster and abstracts of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47th Annual Meeting; October 24-29, 2000; New York, NY.

10.Okie S. ADHD in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;25:2637-2641.

11.Solden S. Women with Attention Deficit Disorder. Grass Valley, Calif: Underwood Books; 1995.

12.Nadeau K, Quinn P. The history of ADHD -- an unexamined gender bias. In: Quinn PO, Nadeau KG, eds. Gender Issues and ADHD: Research, Diagnosis and Treatment. Silver Spring, Md: Advantage Books; 2002:2-22.

13.Kelly J. Depression often misdiagnosed in primary care. Available at: /viewarticle/706714 Accessed December 7, 2009.

14.Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a Star*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905-1917. Abstract

15.McIntyre R. Bipolar disorder and ADHD: clinical concerns. CNS Spectr. 2009;14:8-9.

16.Atmaca M, Ozler S, Topuz M, Goldstein S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder erroneously diagnosed and treated as bipolar disorder. J Atten Disord. 2009;13:197-198. Abstract

17.Young J. Women with ADHD: unique presentations and treatment approaches. Available at: http://cme.medscape.com/viewarticle/711520_print Accessed December 7, 2009.

18.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006:163:716-723. Abstract

19.Geller D, Donnelly C, Lopez F, et al. Atomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder. J Am Adolesc Psychiatry Acad Child. 2007;46:1119-1127.

20.Young J. Oros-methylphenidate added to fluoxetine in treatment-resistant depression. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association's 58th Institute on Psychiatric Services, October 2006; New York, NY.

21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ADHD Data & Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncgbddd/adhd/data.html Accessed November 8, 2009.