Exploring the Hidden Cause

excerpted from Living With the Devil We Know

by David Burns

At first, I thought that Margaret's case was just an isolated example, but over time, I began to notice the same pattern with more and more anxious patients who seemed stuck. I started asking them if there was something going on in their lives that they hadn't told me about--something that was bothering them. At first, they'd all deny it, but after a few sessions, a hidden emotion or problem would emerge. When the patient expressed the hidden feeling or took steps to solve the problem he or she had been avoiding, the anxiety improved significantly or, more often, disappeared completely, just as in Margaret's case. It seemed that these patients were trying to teach me something important about the deeper causes of anxiety, something that wasn't a part of my CBT training. They were giving me a new tool I decided to call the Hidden Emotion Technique.

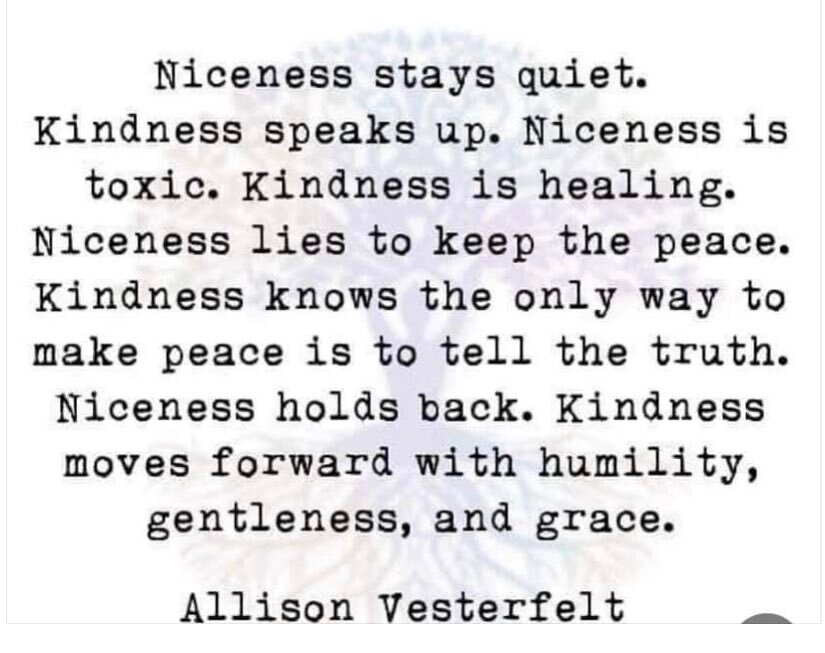

The vast majority of these patients were exceptionally nice individuals who felt a strong urge to please others. In fact, most of them seemed to exhibit-beneath their panic attacks, anxieties, and fears-phobias about conflict, anger, or negative emotions of any kind. They seemed to experience a kind of emotional perfectionism, the belief that they should always be happy, pleasant, calm, and totally in control of their feelings, even at the expense of their own desires and emotional needs.

In other words, when anxiety-prone individuals get feelings or urges that don't seem "proper" or "acceptable," they sweep them under the rug without realizing they're doing this. Then they suddenly develop a phobia, a panic attack, or OCD symptoms and completely lose sight of the hidden problem or feeling that triggered the anxiety in the first place. This dynamic isn't always happening-sometimes a phobia is just a phobia-but through the years, I've observed it in roughly 75 percent of my anxious patients, and when I help them uncover the hidden emotion, the anxiety disappears with astonishing regularity.

As I thought back to my own childhood and life, I noticed this pattern as well. When I was growing up, I struggled with all kinds of fears and phobias. I feared bees, dogs, horses, blood, heights, vomiting, cameras, public speaking, social occasions, and more. Why had I been so afraid of so many things?

Like so many of my anxious patients, I've felt a strong urge to be nice. I'm not entirely sure where it came from, but I was what's known as a PK, or "preacher's kid." My father was a Lutheran minister and a basically kind man, but strict, demanding that his children adhere to a fairly rigid formula of "goodness." We were expected not just to follow rules, but to follow them in a humble spirit, always to be polite and considerate, to please others, and to be models of good behavior. To this day, when I'm beginning to feel a sense of dread or generalized anxiety about my life, it's usually because I'm feeling annoyed with someone, or upset about something, that I'm sweeping under the carpet--because I think I'm not "allowed" to have those kinds of negative feelings. When I bring the problem to conscious awareness and deal with it, in most cases, the anxiety immediately disappears.

You might call this the Excessive Niceness Syndrome, and it's made me think about anxiety and phobias in ways much different from those I was taught during my psychiatric training. We commonly refer to phobias, panic attacks, and obsessive worrying as symptoms of anxiety disorders, as if they were mysterious pathological conditions without any meaningful connection to the emotional life of the person who's experiencing them. In fact, we're sometimes taught that depression and anxiety result from some type of chemical imbalance in the brain, although that theory has never been validated. Now I'm inclined to view anxiety as part and parcel of the human condition. Specifically, I wonder whether anxiety might ultimately result from a kind of existential fear of the self--fear of who we are and how we really feel as human beings. Perhaps these phobias and fears serve the purpose of safely isolating us from uncontrollable urges, feelings, desires, and impulses that we dislike and that contradict our idealized notions of who we think we are or should be.

From my work with large numbers of clients with every conceivable type of anxiety, I've learned more about the nature of the hidden problems that trigger the symptoms. First, the problem is almost never buried in the past. It's something that's bothering the client in the here and now. Second, it's something obvious and simple, like hating law school, but feeling you have to stay in law school because your father always wanted you to be a lawyer. Third, it's usually a symbolic expression of the hidden conflict. For example, the law student with panic attacks doesn't have to say, "Dad, I've decided to drop out of law school because I don't want to be a lawyer. I want to become a journalist." Instead, by assuming the sick role, the student can say, in essence, "I just can't continue with law school because I'm going crazy: I'm on the verge of a nervous breakdown." This symbolism isn't created at the conscious level, of course. Anxiety is a kind of creative poetry that the brain automatically generates, much like dreaming. As a therapist, you have to "listen" to the poem to detect the symbolic meaning.

Although the Hidden Emotion Technique appears to me to be a significant advance in the treatment of anxiety, I don't mean to minimize the enormous contributions of the many brilliant therapists who've developed CBT and other new forms of psychotherapy. I'm proud of my own contributions to CBT and still enthusiastically use its techniques with every depressed and anxious individual I treat. But I now have a new model, which seems to illuminate some of the whys and whens of anxiety, along with a powerful new treatment tool to help dislodge anxious clients who've gotten stuck with only partial improvement when I've used more traditional forms of CBT.

excerpted from Living With the Devil We Know

by David Burns

At first, I thought that Margaret's case was just an isolated example, but over time, I began to notice the same pattern with more and more anxious patients who seemed stuck. I started asking them if there was something going on in their lives that they hadn't told me about--something that was bothering them. At first, they'd all deny it, but after a few sessions, a hidden emotion or problem would emerge. When the patient expressed the hidden feeling or took steps to solve the problem he or she had been avoiding, the anxiety improved significantly or, more often, disappeared completely, just as in Margaret's case. It seemed that these patients were trying to teach me something important about the deeper causes of anxiety, something that wasn't a part of my CBT training. They were giving me a new tool I decided to call the Hidden Emotion Technique.

The vast majority of these patients were exceptionally nice individuals who felt a strong urge to please others. In fact, most of them seemed to exhibit-beneath their panic attacks, anxieties, and fears-phobias about conflict, anger, or negative emotions of any kind. They seemed to experience a kind of emotional perfectionism, the belief that they should always be happy, pleasant, calm, and totally in control of their feelings, even at the expense of their own desires and emotional needs.

In other words, when anxiety-prone individuals get feelings or urges that don't seem "proper" or "acceptable," they sweep them under the rug without realizing they're doing this. Then they suddenly develop a phobia, a panic attack, or OCD symptoms and completely lose sight of the hidden problem or feeling that triggered the anxiety in the first place. This dynamic isn't always happening-sometimes a phobia is just a phobia-but through the years, I've observed it in roughly 75 percent of my anxious patients, and when I help them uncover the hidden emotion, the anxiety disappears with astonishing regularity.

As I thought back to my own childhood and life, I noticed this pattern as well. When I was growing up, I struggled with all kinds of fears and phobias. I feared bees, dogs, horses, blood, heights, vomiting, cameras, public speaking, social occasions, and more. Why had I been so afraid of so many things?

Like so many of my anxious patients, I've felt a strong urge to be nice. I'm not entirely sure where it came from, but I was what's known as a PK, or "preacher's kid." My father was a Lutheran minister and a basically kind man, but strict, demanding that his children adhere to a fairly rigid formula of "goodness." We were expected not just to follow rules, but to follow them in a humble spirit, always to be polite and considerate, to please others, and to be models of good behavior. To this day, when I'm beginning to feel a sense of dread or generalized anxiety about my life, it's usually because I'm feeling annoyed with someone, or upset about something, that I'm sweeping under the carpet--because I think I'm not "allowed" to have those kinds of negative feelings. When I bring the problem to conscious awareness and deal with it, in most cases, the anxiety immediately disappears.

You might call this the Excessive Niceness Syndrome, and it's made me think about anxiety and phobias in ways much different from those I was taught during my psychiatric training. We commonly refer to phobias, panic attacks, and obsessive worrying as symptoms of anxiety disorders, as if they were mysterious pathological conditions without any meaningful connection to the emotional life of the person who's experiencing them. In fact, we're sometimes taught that depression and anxiety result from some type of chemical imbalance in the brain, although that theory has never been validated. Now I'm inclined to view anxiety as part and parcel of the human condition. Specifically, I wonder whether anxiety might ultimately result from a kind of existential fear of the self--fear of who we are and how we really feel as human beings. Perhaps these phobias and fears serve the purpose of safely isolating us from uncontrollable urges, feelings, desires, and impulses that we dislike and that contradict our idealized notions of who we think we are or should be.

From my work with large numbers of clients with every conceivable type of anxiety, I've learned more about the nature of the hidden problems that trigger the symptoms. First, the problem is almost never buried in the past. It's something that's bothering the client in the here and now. Second, it's something obvious and simple, like hating law school, but feeling you have to stay in law school because your father always wanted you to be a lawyer. Third, it's usually a symbolic expression of the hidden conflict. For example, the law student with panic attacks doesn't have to say, "Dad, I've decided to drop out of law school because I don't want to be a lawyer. I want to become a journalist." Instead, by assuming the sick role, the student can say, in essence, "I just can't continue with law school because I'm going crazy: I'm on the verge of a nervous breakdown." This symbolism isn't created at the conscious level, of course. Anxiety is a kind of creative poetry that the brain automatically generates, much like dreaming. As a therapist, you have to "listen" to the poem to detect the symbolic meaning.

Although the Hidden Emotion Technique appears to me to be a significant advance in the treatment of anxiety, I don't mean to minimize the enormous contributions of the many brilliant therapists who've developed CBT and other new forms of psychotherapy. I'm proud of my own contributions to CBT and still enthusiastically use its techniques with every depressed and anxious individual I treat. But I now have a new model, which seems to illuminate some of the whys and whens of anxiety, along with a powerful new treatment tool to help dislodge anxious clients who've gotten stuck with only partial improvement when I've used more traditional forms of CBT.