Oliver Sacks: His Own Life

Medscape Medical News

February 19, 2015

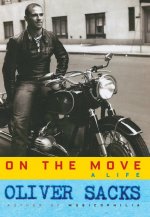

Dr Oliver Sacks

After years of tackling difficult neurologic conditions in his practice and his writings, British-born neurologist Oliver Sacks, MD, addresses another disease in an essay today in the New York Times ? his own terminal illness.

In it, Dr Sacks, a professor of neurology at the New York University School of Medicine and author of many popular books, including Awakenings (which was made into a major motion picture) and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, discusses his diagnosis and his plans for the time he has left.

"A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health," Dr Sacks writes. "At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out -- a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver.

"Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. Although the radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye, only in very rare cases do such tumors metastasize. I am among the unlucky 2%.

"I feel grateful that I have been granted nine years of good health and productivity since the original diagnosis, but now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

"It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me," he writes. "I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can."

In this, he says he is encouraged by the words of David Hume, who, upon learning of his own terminal illness, wrote his autobiography in a single day in April 1776. The biography was titled My Own Life, a title also used for this essay.

In it, Hume wrote of his good spirits in the face of his bodily decline, with "the same ardour as ever in study, and the same gaiety in company."

Dr Sacks counts himself lucky to have lived 15 years beyond Hume's 65, years that "have been equally rich in work and love," he writes. "In that time, I have published five books and completed an autobiography (rather longer than Hume's few pages) to be published this spring. I have several other books nearly finished."

In the time he has left to him, he hopes "to deepen my friendships, say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight."

He plans no longer to pay attention to things like politics or arguments about global warming, not because he doesn't care deeply, he writes, but because "these are no longer my business; they belong to the future."

Dr Sacks' full editorial can be found here.

Medscape Medical News

February 19, 2015

Dr Oliver Sacks

After years of tackling difficult neurologic conditions in his practice and his writings, British-born neurologist Oliver Sacks, MD, addresses another disease in an essay today in the New York Times ? his own terminal illness.

In it, Dr Sacks, a professor of neurology at the New York University School of Medicine and author of many popular books, including Awakenings (which was made into a major motion picture) and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, discusses his diagnosis and his plans for the time he has left.

"A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health," Dr Sacks writes. "At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out -- a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver.

"Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma. Although the radiation and lasering to remove the tumor ultimately left me blind in that eye, only in very rare cases do such tumors metastasize. I am among the unlucky 2%.

"I feel grateful that I have been granted nine years of good health and productivity since the original diagnosis, but now I am face to face with dying. The cancer occupies a third of my liver, and though its advance may be slowed, this particular sort of cancer cannot be halted.

"It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me," he writes. "I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can."

In this, he says he is encouraged by the words of David Hume, who, upon learning of his own terminal illness, wrote his autobiography in a single day in April 1776. The biography was titled My Own Life, a title also used for this essay.

In it, Hume wrote of his good spirits in the face of his bodily decline, with "the same ardour as ever in study, and the same gaiety in company."

Dr Sacks counts himself lucky to have lived 15 years beyond Hume's 65, years that "have been equally rich in work and love," he writes. "In that time, I have published five books and completed an autobiography (rather longer than Hume's few pages) to be published this spring. I have several other books nearly finished."

In the time he has left to him, he hopes "to deepen my friendships, say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight."

He plans no longer to pay attention to things like politics or arguments about global warming, not because he doesn't care deeply, he writes, but because "these are no longer my business; they belong to the future."

Dr Sacks' full editorial can be found here.