desiderata

Member

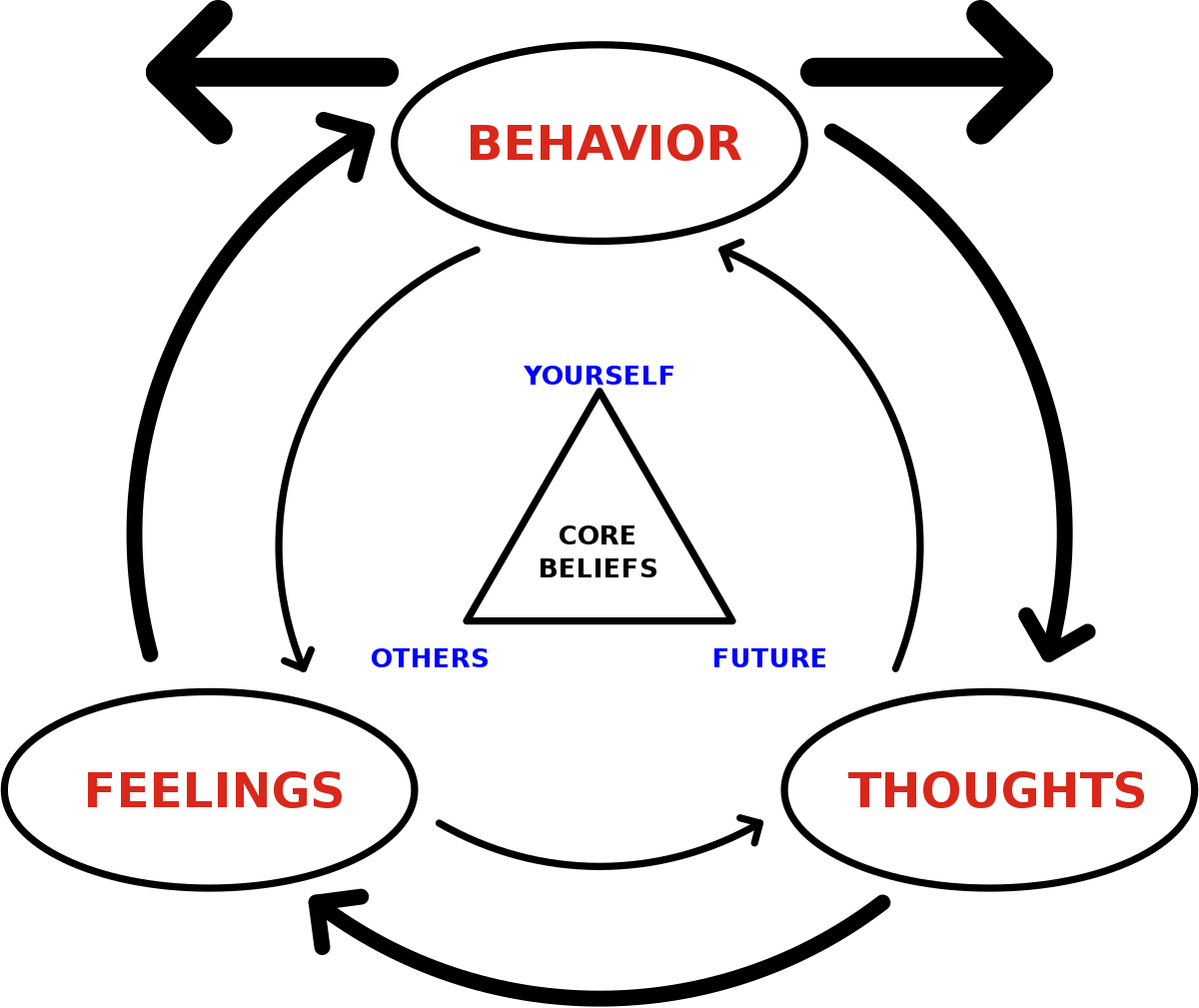

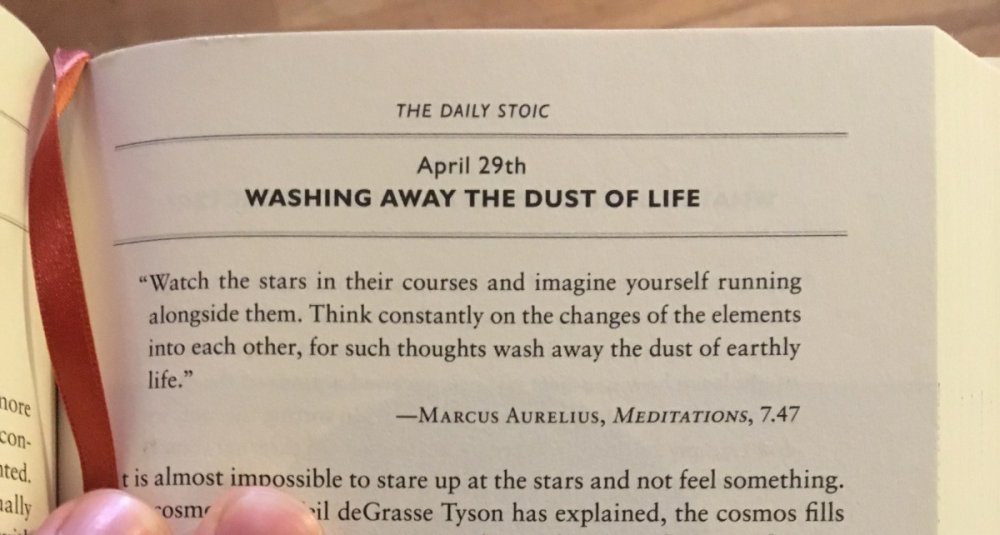

I have recently taken to the teachings of stoicism- A school of Greek philosophy and wisdom. The teachings have revealed what is mostly known to me yet is refreshing when put into a format and context spoken or written by some of the great minds in history. Mindfulness being in the forefront. My question to the panel is does stoicism have a place in the world of psychology?