David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

Client Centered Therapy: Why It Works

BetterHelp

Retrieved November 4, 2017

Client centered therapy (CCT) emerged in the 1930s during a time when the neo-Freudians were expanding psychoanalysis, a form of therapy that placed the patient in the center, but not always in a positive manner. Many patients of those who used the Freudian method of therapy found the therapy to be too suggestive, meaning patients left therapy having a diagnosis, but having very little help (Kahn, 2012). Carl Rogers developed the CCT method, it has been called Rogerian as a technique. After the first years, Rogers later changed the name for his style from client centered therapy to person-centered therapy.

Rogers did not want his clients to view themselves as patients, or as a diagnosis. This is one of the reasons the name evolved to person-centered therapy, as Rogers wanted to convey to his clients that he regarded them as persons, and not as an illness or a diagnosis (Friedrich, 2003). Client-centered therapy is most effective for individuals who are experiencing situational stressors, depression, anxiety, or working through issues related to personality disorders (Bowles, 2012).

With client or person centered therapy, the focus is on the individual, and the therapist is a sounding board. The basic tenets of CCT are:

In order for therapy to work, no matter the style of the therapist, the client must not feel as though he or she is subject to judgment (Kahn, 2012). If an individual did not have problems, then he or she would not feel the need to seek therapy. It is not the job of a therapist to form judgments or even opinions that are outside the realm of professionalism. Clients who do not feel judged are generally more comfortable with expression and tend to gain more insight into their own problems while developing a greater ability to resolve them (Friedrich, 2003).

Why Client Centered Therapy Works

Client centered therapy works for all the reasons talking to family, friends, or even clergy do not. It is not always easy to talk to those who know us best, there are times that past actions may become the focus of attention, preventing the individual from talking about the here and now, or the most pressing issues. With client centered therapy, the focus is on what the client needs (Grant, 2010). If a client needs to discuss the past, the therapist will listen and respond in an empathic manner. This is done with the idea that this past issue is impeding the individual's ability to adequately deal with the here and now (Friedrich, 2003). Unlike the therapy clich? of placing blame on parenting, the client centered therapist recognizes that past hurts can play an important role in the ability to work through current issues; however, in order for a person to effectively cope with and overcome current obstacles, they must be given a forum in which to express past pains.

With client centered therapy, clients who have either sought therapy before, or known others who have, are often surprised, and maybe even a bit put off by the fact that the therapist does not ask questions, outside of those seeking clarification, or mirroring what the client has stated (Seehausen, Kazzer, Bajbouj, & Prehn, 2012). Nor does the client centered therapist instruct, or suggest. Instead the client centered therapist realizes that the power of therapy stems from the client forming his or her own insights and making his or her own decisions based on those insights (Kahn, 2012). The goal of client centered therapy fits the adage about teaching someone to fish vs. giving them fish.

Drawing from Theory

Client-Centered Therapy Lets The Patient Lead The Direction of The Session

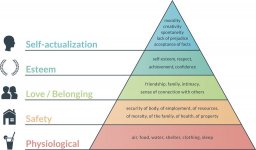

According to Freidrich (2003), one of the tenets client centered therapy draws upon is that of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. According to Maslow, individuals are constantly seeking self-actualization. Self-actualization is when an individual has achieved a point of recognition and comfort of who and what he or she is. This does not mean the person feels that he or she has achieved all that can or could be achieved; the self-actualized individual has arrived at a point where he or she can do the best work, and contribute the most to family, friends, society, education, and/or science. Maslow theorized that in order for a person to ever achieve self-actualization that lower tier needs had to be met first. The first, physical needs, such as nutrition, sleep, and biological needs. The second, safety needs- having adequate housing, clothing, and comfort. The third, belonging needs, that one has an intact family and/or social support system. The fourth, before achieving a level of self-actualization, is that of esteem and self-worth.

Rogers believed that it was when an individual had not had the basic needs met that he or she was in a state of crisis; however, that if belonging needs were met that even if a person lost his or her home and all that was dear that the ability for recovery is there. It is often because belonging needs are unmet that individuals need and thrive from attending client centered therapy (Bowles, 2012).

For Whom and How Client Centered Therapy Works

The instances where client centered therapy is less likely to work is when an individual is undergoing psychosis or in extreme psychological crisis (Grant, 2010). Client centered therapy works best for those clients who have the ability to communicate, remain in the here and now, and put the past into perspective. Individuals who are experiencing hallucinations, delusions, or other breaks with reality are not usually good candidates for client centered therapy (Grant, 2010). This is not because the therapy itself would not work, but because the client needs to be in touch with reality in order for the therapy to work.

Unfortunately, there are few therapists who advertise that they practice client-centered therapy, so it is up to the client to make his or her own determination if the therapist will focus the sessions upon the client's immediate needs vs. ultimate outcomes (Seehausen, Kazzer, Bajbouj, & Prehn, 2012. When a person is in crisis there is an immediate need, a precipitating event that leads to an individual seeking therapy. However, sometimes it is the inability to overcome the past events, such as parental divorce, abuse, or early substance abuse that ultimately leads to the precipitating event. Many therapists refuse to dwell in the past, while others will not speak of the present until the past has been unearthed (Kahn, 2012). The client-centered therapist allows therapy to occur in an organic manner according to the client's needs.

As stated earlier, it is up to the client to conduct some preliminary research to determine if the style of the therapist is right for his or her situation. The wording of a therapist's online or print advertisement, as well as what past clients say in comments/feedback sections are important.

Six Key Elements to Look for in a Therapist's Advertisement or First Session

The Inferences of "Getting Better"

The purpose of going to therapy is not always about "getting better," sometimes it is about accepting who and where a person is in life (Grant, 2010). Oftentimes the view a person has of him or herself is shaped by family or societal expectations. In order to achieve self-actualization, it is important to form self-acceptance (Friedrich, 2003). There is no point to guilt over past mistakes (Bowles, 2012). Once a person has recognized a wrong and taken steps to making amends for it, it is time to move forward. Depending upon others to accept an apology or to recognize an act of contrition is futile. However, individuals find the need for acknowledgment. In the absence of this, it is often difficult for the individual to move forward in the healing process.

With client centered therapy, there is no judgment, leaving the individual free to express guilt, anger, sadness, fear, and any emotion relevant to his or her circumstances (Strawbridge, 2001, 2004). This is often the missing element in personal relationships as people have the tendency to make it all about them when someone voices a feeling, complaint, or recommendation.

Relationships are not easy, whether with the family into which one is born, married into, or through work relationships. The problem with any and all of these is that the persons involved have their own agendas. These agendas often get in the way of communication. With client centered therapy, there are no agendas that are not set by the client.

Conclusions and Recommendations

When seeking a therapist, it is important to recognize that he or she is not the authority on what is best, the therapist is merely a tool to help an individual achieve a level of self-discovery. The therapist is not and should not ever be in a position of power, but rather, a tool for empowerment. Then and only then can a client feel the level of comfort necessary to reveal authentic feelings and thoughts.

Client centered therapy works because it is what works for the client, and not a discharge plan devised by the therapist. The goal of therapy is not always about being cured, it is sometimes simply about acceptance. A client centered therapist is not in a position to demand change, but to encourage acceptance. If an individual realizes through acceptance that change is necessary, then it is his or her choice, and that is healthier than feeling unaccepted, unappreciated, and disrespected.

There are a variety of avenues open to individuals seeking counseling and therapy services today. Choices range from seeking therapy through primary care physician referrals to searching via an insurance provider list. There are also online therapy options, that are not only affordable but are private and convenient. With online therapy services, the therapist knows that it is important to focus the conversations around the here and now and to listen and be in tune with what the client is saying. With online therapy, the client has a choice of email, chat, or video to communicate with a qualified therapist. The comfort level of the client is of the greatest import in the beginning stages of therapy. Having a choice that is convenient, cost-effective, and securely provides a foundation for optimum results.

References

BetterHelp

Retrieved November 4, 2017

Client centered therapy (CCT) emerged in the 1930s during a time when the neo-Freudians were expanding psychoanalysis, a form of therapy that placed the patient in the center, but not always in a positive manner. Many patients of those who used the Freudian method of therapy found the therapy to be too suggestive, meaning patients left therapy having a diagnosis, but having very little help (Kahn, 2012). Carl Rogers developed the CCT method, it has been called Rogerian as a technique. After the first years, Rogers later changed the name for his style from client centered therapy to person-centered therapy.

Rogers did not want his clients to view themselves as patients, or as a diagnosis. This is one of the reasons the name evolved to person-centered therapy, as Rogers wanted to convey to his clients that he regarded them as persons, and not as an illness or a diagnosis (Friedrich, 2003). Client-centered therapy is most effective for individuals who are experiencing situational stressors, depression, anxiety, or working through issues related to personality disorders (Bowles, 2012).

With client or person centered therapy, the focus is on the individual, and the therapist is a sounding board. The basic tenets of CCT are:

- Unconditional positive regard - accepting the client where and how he or she is.

- Congruence - the ability of the therapist to be relatable to the client by dropping the professional facade and being human.

- Empathy - the ability to recognize and respond to emotions expressed by the client.

In order for therapy to work, no matter the style of the therapist, the client must not feel as though he or she is subject to judgment (Kahn, 2012). If an individual did not have problems, then he or she would not feel the need to seek therapy. It is not the job of a therapist to form judgments or even opinions that are outside the realm of professionalism. Clients who do not feel judged are generally more comfortable with expression and tend to gain more insight into their own problems while developing a greater ability to resolve them (Friedrich, 2003).

Why Client Centered Therapy Works

Client centered therapy works for all the reasons talking to family, friends, or even clergy do not. It is not always easy to talk to those who know us best, there are times that past actions may become the focus of attention, preventing the individual from talking about the here and now, or the most pressing issues. With client centered therapy, the focus is on what the client needs (Grant, 2010). If a client needs to discuss the past, the therapist will listen and respond in an empathic manner. This is done with the idea that this past issue is impeding the individual's ability to adequately deal with the here and now (Friedrich, 2003). Unlike the therapy clich? of placing blame on parenting, the client centered therapist recognizes that past hurts can play an important role in the ability to work through current issues; however, in order for a person to effectively cope with and overcome current obstacles, they must be given a forum in which to express past pains.

With client centered therapy, clients who have either sought therapy before, or known others who have, are often surprised, and maybe even a bit put off by the fact that the therapist does not ask questions, outside of those seeking clarification, or mirroring what the client has stated (Seehausen, Kazzer, Bajbouj, & Prehn, 2012). Nor does the client centered therapist instruct, or suggest. Instead the client centered therapist realizes that the power of therapy stems from the client forming his or her own insights and making his or her own decisions based on those insights (Kahn, 2012). The goal of client centered therapy fits the adage about teaching someone to fish vs. giving them fish.

Drawing from Theory

Client-Centered Therapy Lets The Patient Lead The Direction of The Session

According to Freidrich (2003), one of the tenets client centered therapy draws upon is that of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. According to Maslow, individuals are constantly seeking self-actualization. Self-actualization is when an individual has achieved a point of recognition and comfort of who and what he or she is. This does not mean the person feels that he or she has achieved all that can or could be achieved; the self-actualized individual has arrived at a point where he or she can do the best work, and contribute the most to family, friends, society, education, and/or science. Maslow theorized that in order for a person to ever achieve self-actualization that lower tier needs had to be met first. The first, physical needs, such as nutrition, sleep, and biological needs. The second, safety needs- having adequate housing, clothing, and comfort. The third, belonging needs, that one has an intact family and/or social support system. The fourth, before achieving a level of self-actualization, is that of esteem and self-worth.

Rogers believed that it was when an individual had not had the basic needs met that he or she was in a state of crisis; however, that if belonging needs were met that even if a person lost his or her home and all that was dear that the ability for recovery is there. It is often because belonging needs are unmet that individuals need and thrive from attending client centered therapy (Bowles, 2012).

For Whom and How Client Centered Therapy Works

The instances where client centered therapy is less likely to work is when an individual is undergoing psychosis or in extreme psychological crisis (Grant, 2010). Client centered therapy works best for those clients who have the ability to communicate, remain in the here and now, and put the past into perspective. Individuals who are experiencing hallucinations, delusions, or other breaks with reality are not usually good candidates for client centered therapy (Grant, 2010). This is not because the therapy itself would not work, but because the client needs to be in touch with reality in order for the therapy to work.

Unfortunately, there are few therapists who advertise that they practice client-centered therapy, so it is up to the client to make his or her own determination if the therapist will focus the sessions upon the client's immediate needs vs. ultimate outcomes (Seehausen, Kazzer, Bajbouj, & Prehn, 2012. When a person is in crisis there is an immediate need, a precipitating event that leads to an individual seeking therapy. However, sometimes it is the inability to overcome the past events, such as parental divorce, abuse, or early substance abuse that ultimately leads to the precipitating event. Many therapists refuse to dwell in the past, while others will not speak of the present until the past has been unearthed (Kahn, 2012). The client-centered therapist allows therapy to occur in an organic manner according to the client's needs.

As stated earlier, it is up to the client to conduct some preliminary research to determine if the style of the therapist is right for his or her situation. The wording of a therapist's online or print advertisement, as well as what past clients say in comments/feedback sections are important.

Six Key Elements to Look for in a Therapist's Advertisement or First Session

- Therapist-Client Psychological Contact: The therapist must indicate that knowing the client and establishing a client-therapist relationship that it based upon authenticity is key.

- Client Incongruence or Vulnerability: The therapist recognizes the incongruence between self-image and the reality of the here and now, and responds with empathy, and not judgment.

- Therapist Congruence or Genuineness: The therapist is genuine, empathic, and does not allow professionalism to cloud the ability to demonstrate authentic feelings while still maintaining an ethical demeanor.

- Therapist Unconditional Positive Regard: The therapist accepts the client for who and where her or she is, recognizing that getting beyond the current is a process.

- Therapist Empathy: The therapist can remain detached, while still expressing empathy and understanding toward the client and his or her experiences.

- Client Perception: The client recognizes that even though he or she is uncomfortable with his or her present state, that the therapist accepts, and respects who he or she is, and what his or her experiences are in the present. (Friedrich, 2003)

The Inferences of "Getting Better"

The purpose of going to therapy is not always about "getting better," sometimes it is about accepting who and where a person is in life (Grant, 2010). Oftentimes the view a person has of him or herself is shaped by family or societal expectations. In order to achieve self-actualization, it is important to form self-acceptance (Friedrich, 2003). There is no point to guilt over past mistakes (Bowles, 2012). Once a person has recognized a wrong and taken steps to making amends for it, it is time to move forward. Depending upon others to accept an apology or to recognize an act of contrition is futile. However, individuals find the need for acknowledgment. In the absence of this, it is often difficult for the individual to move forward in the healing process.

With client centered therapy, there is no judgment, leaving the individual free to express guilt, anger, sadness, fear, and any emotion relevant to his or her circumstances (Strawbridge, 2001, 2004). This is often the missing element in personal relationships as people have the tendency to make it all about them when someone voices a feeling, complaint, or recommendation.

Relationships are not easy, whether with the family into which one is born, married into, or through work relationships. The problem with any and all of these is that the persons involved have their own agendas. These agendas often get in the way of communication. With client centered therapy, there are no agendas that are not set by the client.

Conclusions and Recommendations

When seeking a therapist, it is important to recognize that he or she is not the authority on what is best, the therapist is merely a tool to help an individual achieve a level of self-discovery. The therapist is not and should not ever be in a position of power, but rather, a tool for empowerment. Then and only then can a client feel the level of comfort necessary to reveal authentic feelings and thoughts.

Client centered therapy works because it is what works for the client, and not a discharge plan devised by the therapist. The goal of therapy is not always about being cured, it is sometimes simply about acceptance. A client centered therapist is not in a position to demand change, but to encourage acceptance. If an individual realizes through acceptance that change is necessary, then it is his or her choice, and that is healthier than feeling unaccepted, unappreciated, and disrespected.

There are a variety of avenues open to individuals seeking counseling and therapy services today. Choices range from seeking therapy through primary care physician referrals to searching via an insurance provider list. There are also online therapy options, that are not only affordable but are private and convenient. With online therapy services, the therapist knows that it is important to focus the conversations around the here and now and to listen and be in tune with what the client is saying. With online therapy, the client has a choice of email, chat, or video to communicate with a qualified therapist. The comfort level of the client is of the greatest import in the beginning stages of therapy. Having a choice that is convenient, cost-effective, and securely provides a foundation for optimum results.

References

- Bowles, T. (2012). Developing Adaptive Change Capabilities Through Client-Centred Therapy. Behaviour Change; Bowen Hills, 29(4), 258-271.

- Gon?alves, M. M., Mendes, I., Cruz, G., Ribeiro, A. P., Sousa, I., Angus, L., & Greenberg, L. S. (2012). Innovative moments and change in client-centered therapy. Psychotherapy Research: Journal Of The Society For Psychotherapy Research, 22(4), 389-401.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.662605 - Grant, B. (2010). Getting the Point: Empathic Understanding in Nondirective Client-Centered Therapy. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 9(3), 220-235.

- Kahn, E. (2012). On being "up to other things": The nondirective attitude and therapist-frame responses in client-centered therapy and contemporary psychoanalysis. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 11(3), 240-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2012.700285

- Seehausen, M., Kazzer, P., Bajbouj, M., & Prehn, K. (2012). Effects of Empathic Paraphrasing - Extrinsic Emotion Regulation in Social Conflict.

Frontiers in Psychology, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00482 - Strawbridge, S. (2001, 04). Carl rogers. Psychologist, 14, 185. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/211837881?accountid=458