David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

Is exercise the new snake oil? or just a dirty word?

by Bronnie Lennox Thompson, HealthSkills BlogAug 10, 2020

If you haven’t heard about the health benefits of exercise in the last 10 years or longer, then you’ve probably been a hermit! Exercise can do all these wonderful things – help you lose weight, reduce heart disease, moderate insulin and blood glucose levels, improve your mental health, and yes! reduce pain and disability when you’re sore. (check this list out)

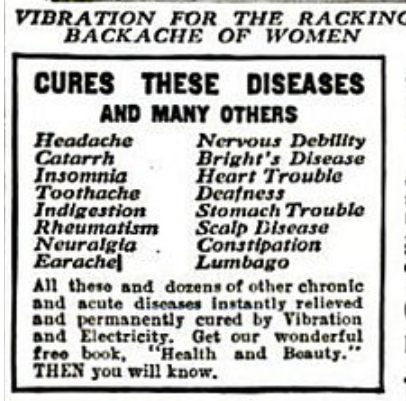

The claims sound suspiciously similar to the claims made by old snake oil merchants – or the amazing White Cross Electric Vibrator!

Well perhaps there’s a little more research supporting claims for exercise… but are those claims being inflated just a little? When it comes to pain, particularly persistent pain, perhaps so…

But before I launch into some of the problems with exercise research, I have another problem with “exercise” – and that’s the word itself.

According to Wikipedia (and no, it’s not an academic reference!!) “Exercise is any bodily activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.” Winter and Fowler (2009) in an interesting paper looking at definitions of exercise, found that “exercise” and “physical activity” are essentially the same and differ only in terms of motivation/intent, finally arriving at this definition: “A potential disruption to homeostasis by muscle activity that is either exclusively or in combination, concentric, isometric or eccentric.” Whew! Glad we’ve got this sorted.

But given the sticky nature of our minds, and that very few of us are inclined to spend hours debating the technical details, the word “exercise” has picked up quite a few other meanings. For me it conjures up images of sweaty, lycra-clad blokes grunting in front of enormous mirrors while they heave on lumps of metal to the pumping rhythm of loud music (and the eyes that follow my every move). It also raises the spectre of school sports where I was inevitably the last person chosen for any sports team, the last to come in after every run, the person who got hit in the face by the ball, who got her thumb smacked by the hockey stick the week before my piano exams…

I’m not alone in my distaste for “exercise”. Qualitative researchers have often investigated how people with pain view exercise: “I get the comments that “It is not dangerous” and that “you are not going to be worse.” I do not believe it is dangerous … but actually it happens that I become worse after .… I know that the pain will increase. And they … talk to me about pain that is not like my pain.” (Karlsson, Gerdle, Takala, Andersson & Larsson, 2018)

Boutevillain, Dupeyron, Rouch, Riuchard & Coudeyre (2017) in another qualitative study, found that people with low back pain firstly identified that pain intensity interfered “any minimal physical activity, standing still in one spot, is torture” (line 1683); “if my back hurts, I don’t do any activity that’s for sure, I am not going to the garden and do some digging, that is out of the question! I have two children, if I am in pain and they want to play, my back hurts and I can’t play with them. My back hurts I can’t do it. It’s not that I don’t want to it is just that I cannot. I am unable to” (line 29). In turn, motivation for exercise was reduced “I don’t have any desire to exercise. A lack of motivation, even apprehension” (line 390); “there needs to be this spark to get motivated, and I just don’t have it” (line 1335). Along with the lack of perceived benefits for some: “Sometimes I try to exercise and then I’m in pain, looking back had I known it would hurt I would probably not have done it” (line 2037) “It can be harmful, I give you an example: I have a colleague with low back problems, similar to mine, and she loves to take step classes, but each time she exercises too much, she is in pain but continues. I think she should stop, it is quite dangerous for her” (line 378).

A systematic review by Slade, Patel, Underwood and Keating (2014) found that “Individuals were more likely to engage within programs that were fun and had variety than ones that were boring, unchallenging, or onerous because they disrupted daily activities.” They added that “Difficulties with exercise adherence and not seeing benefits of exercise were frequently attributed to lack of time and fit into daily life.” Quotes drawn from the studies included in this review show that lack of confidence, negative experiences at the time, and poor “fit” between the exercises selected and individual preferences influence whether exercise was carried out consistently.

At the same time as these negative views, many participants in qualitative studies report that they use “movement” as a key strategy for their daily management. Whether movement looked like “exercise” as prescribed by PTs or trainers is a little less clear – people use the word “exercise” to mean many different things, hence Karlsson and colleagues (2018) combined the term “physical activity and exercise”.

Now one very important point about exercise, and one that’s rarely mentioned, is how little exercise actually reduces pain – and disability. A systematic review of systematic reviews from the Cochrane collaboration found that most studies included people with mild-to-moderate pain (less than 30/100 on a VAS) but the results showed pain reduction of around 10mm on a 0 – 100mm scale. In terms of physical function, significant improvements were identified but these were small to moderate in size.

And let’s not talk about the quality of those studies! Sadly, methodological problems plague studies into exercise, particularly sample size. Most studies are quite small, which can lead to over-estimating the benefits, while biases associated with randomisation, blinding and attrition rate/drop-outs, adherence and adverse effects.

Before anyone starts getting crabby about this blog post, here are my key points (and why I’ve taken this topic on!):

- Over-stating the effects of exercise won’t win you friends. It creates an atmosphere where those who don’t obtain pain reduction can feel pretty badly about it. Let’s be honest that effects on pain reduction and disability are not all that wonderful. There are other reasons to move!

- Exercise and physical activity can be done in a myriad of wonderful ways, research studies use what’s measurable and controllable – but chasing a puppy at the beach, dancing the salsa, cycling to work, vacuuming the house, three hours of gardening and walking around the shopping mall are all movement opportunities up for grabs. Don’t resort to boring stuff! Get creative (need help with that? Talk to your occupational therapists!).

- The reasons for doing exercise are enormously variable. I move because I love the feeling of my body in rhythm with the music, the wrench of those weeds as they get ripped from my garden, the stretch of my stride as I walk across the park, the ridiculousness of my dog hurtling after a ball… And because I am a total fidget and always have been. Exercise might be “corrective”, to increase cardiovascular fitness, because it’s part of someone’s self-concept, to gain confidence for everyday activities, to beat a record or as part of being a good role model. Whatever the reason, tapping into that is more important than the form of the exercise.

- Without some carryover into daily life (unless the exercise is intrinsically pleasurable), exercise is a waste of time. So if you’re not enjoying the 3 sets of 10 you’ve been given (or you’ve prescribed to someone), think about how it might translate into everyday life. It might be time to change the narrative about movement away from repetitive, boring exercises “for the good of your heart/diabetes/back” and towards whatever larger, values-based orientation switches the “on” switch for this person. And if you’re the person – find some movement options that you like. Exercise snacks through the day. Jiggles to the music (boogie down). Gardening. Swimming. Flying a kite. Don’t be limited by what is the current fashion for lycra and sweaty people lifting heavy things with that loud music pumping in the background.

References

Boutevillain, L., Dupeyron, A., Rouch, C., Richard, E., & Coudeyre, E. (2017). Facilitators and barriers to physical activity in people with chronic low back pain: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 12(7), e0179826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179826

Edward M. Winter & Neil Fowler (2009) Exercise defined and quantified

according to the Système International d’Unités, Journal of Sports Sciences, 27:5, 447-460, DOI: 10.1080/02640410802658461

Geneen, L. J., Moore, R. A., Clarke, C., Martin, D., Colvin, L. A., & Smith, B. H. (2017). Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4, CD011279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3

Karlsson, L., Gerdle, B., Takala, E. P., Andersson, G., & Larsson, B. (2018). Experiences and attitudes about physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic pain: a qualitative interview study. J Pain Res, 11, 133-144. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S149826