The Role of Passion in Sustainable Psychological Well-Being

by Robert J. Vallerand

March 21, 2012

Using the Dualistic Model of Passion (DMP), the purpose of the present paper is to show the role of passion for activities in sustainable psychological well-being. Passion is defined as a strong inclination toward a self-defining activity that people like (or even love), find important, and in which they invest time and energy on a regular basis. The model proposes the existence of two types of passion: harmonious and obsessive. Harmonious passion originates from an autonomous internalization of the activity into one’s identity while obsessive passion emanates from a controlled internalization and comes to control the person. Through the experience of positive emotions during activity engagement that takes place on a regular and repeated basis, it is posited that harmonious passion contributes to sustained psychological well-being while preventing the experience of negative affect, psychological conflict, and ill-being. Obsessive passion is not expected to produce such positive effects and may even facilitate negative affect, conflict with other life activities, and psychological ill-being. Research supporting the proposed effects and processes is presented and directions for future research are proposed...

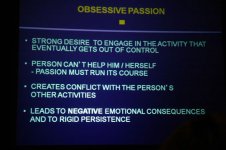

Obsessive passion results from a controlled internalization of the activity into one’s identity and self. A controlled internalization originates from intra and/or interpersonal pressure typically because certain contingencies are attached to the activity such as feelings of social acceptance or self-esteem (see Mageau, Carpentier, & Vallerand, in press), or because the sense of excitement derived from activity engagement is uncontrollable. People with an obsessive passion can thus find themselves in the position of experiencing an uncontrollable urge to partake in the activity they view as important and enjoyable. The passion for the activity comes to control the person. They cannot help but to engage in the passionate activity leading to rigid persistence toward the activity. While such rigid persistence may at times lead to some benefits (e.g., improvement on the activity over time), it may also incur some costs, potentially leading to less than optimal functioning within the confines of the passionate activity because of the lack of flexibility that it entails. Such a rigid and defensive style should lead to self-closure from intrapersonal and interpersonal experiences (Aron, Aron, & Smolan, 1992), to a poor integrative experience during task engagement (Hodgins & Knee, 2002), and thus to negative emotional experiences, while reducing the positive affective outcomes that would normally be experienced (Hodgins & Knee, 2002). Furthermore, such a rigid persistence may lead to the experience of conflict with other aspects of the person’s life when engaging in the passionate activity (when one should be doing something else, for instance), as well as to frustration and rumination about the activity when prevented from engaging in it because of the lost opportunity.

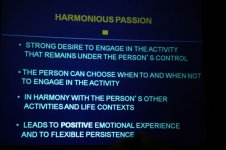

Conversely, harmonious passion results from an autonomous internalization of the activity representation into the person’s identity. An autonomous internalization occurs when individuals have freely accepted the activity as important for them without any or little contingencies attached to it. This type of internalization emanates from the intrinsic and integrative tendencies of the self (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2003). It produces a motivational force to engage in the activity willingly and engenders a sense of volition and personal endorsement about pursuing the activity. When harmonious passion is at play, individuals do not experience an uncontrollable urge to engage in the passionate activity, but rather freely choose to do so. With this type of passion, the activity occupies a significant but not overpowering space in the person’s identity and is in harmony with other aspects of the person’s life. In other words, with harmonious passion the authentic integrating self (Deci & Ryan, 2000) is at play allowing the person to fully partake in the passionate activity with a flexibility and a mindful (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007) open manner that is conducive to positive experiences (Hodgins & Knee, 2002)...

Full Text (Open Access)

by Robert J. Vallerand

March 21, 2012

Using the Dualistic Model of Passion (DMP), the purpose of the present paper is to show the role of passion for activities in sustainable psychological well-being. Passion is defined as a strong inclination toward a self-defining activity that people like (or even love), find important, and in which they invest time and energy on a regular basis. The model proposes the existence of two types of passion: harmonious and obsessive. Harmonious passion originates from an autonomous internalization of the activity into one’s identity while obsessive passion emanates from a controlled internalization and comes to control the person. Through the experience of positive emotions during activity engagement that takes place on a regular and repeated basis, it is posited that harmonious passion contributes to sustained psychological well-being while preventing the experience of negative affect, psychological conflict, and ill-being. Obsessive passion is not expected to produce such positive effects and may even facilitate negative affect, conflict with other life activities, and psychological ill-being. Research supporting the proposed effects and processes is presented and directions for future research are proposed...

Obsessive passion results from a controlled internalization of the activity into one’s identity and self. A controlled internalization originates from intra and/or interpersonal pressure typically because certain contingencies are attached to the activity such as feelings of social acceptance or self-esteem (see Mageau, Carpentier, & Vallerand, in press), or because the sense of excitement derived from activity engagement is uncontrollable. People with an obsessive passion can thus find themselves in the position of experiencing an uncontrollable urge to partake in the activity they view as important and enjoyable. The passion for the activity comes to control the person. They cannot help but to engage in the passionate activity leading to rigid persistence toward the activity. While such rigid persistence may at times lead to some benefits (e.g., improvement on the activity over time), it may also incur some costs, potentially leading to less than optimal functioning within the confines of the passionate activity because of the lack of flexibility that it entails. Such a rigid and defensive style should lead to self-closure from intrapersonal and interpersonal experiences (Aron, Aron, & Smolan, 1992), to a poor integrative experience during task engagement (Hodgins & Knee, 2002), and thus to negative emotional experiences, while reducing the positive affective outcomes that would normally be experienced (Hodgins & Knee, 2002). Furthermore, such a rigid persistence may lead to the experience of conflict with other aspects of the person’s life when engaging in the passionate activity (when one should be doing something else, for instance), as well as to frustration and rumination about the activity when prevented from engaging in it because of the lost opportunity.

Conversely, harmonious passion results from an autonomous internalization of the activity representation into the person’s identity. An autonomous internalization occurs when individuals have freely accepted the activity as important for them without any or little contingencies attached to it. This type of internalization emanates from the intrinsic and integrative tendencies of the self (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2003). It produces a motivational force to engage in the activity willingly and engenders a sense of volition and personal endorsement about pursuing the activity. When harmonious passion is at play, individuals do not experience an uncontrollable urge to engage in the passionate activity, but rather freely choose to do so. With this type of passion, the activity occupies a significant but not overpowering space in the person’s identity and is in harmony with other aspects of the person’s life. In other words, with harmonious passion the authentic integrating self (Deci & Ryan, 2000) is at play allowing the person to fully partake in the passionate activity with a flexibility and a mindful (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007) open manner that is conducive to positive experiences (Hodgins & Knee, 2002)...

Full Text (Open Access)