"If overeating is an addiction, why isn't just plain eating an addiction?" ~ David Baxter

"We uncovered no clear relationship between weight loss and health outcomes related to hypertension, diabetes, or cholesterol,

calling into questions whether weight change per se had any causal role in the effects of the diets. Increased exercise, healthier

eating, engagement with health care system and social support may have played a role instead." ~ Tomiyama, Ahlstrom and Mann

"We envision a world where BMI does not exist." ~ The Association for Size Diversity and Health

"Some of the health effects of the obesity epidemic are related to the way we see our bodies." ~ Muennig et al

"You cannot eat your way into T2D [type 2 diabetes]." ~ HAES Health Sheets

"A future without fat is a dystopian aspiration. And it’s one that fails to acknowledge

the essential role fat plays in our bodies and in the body politic." ~ The Conversation

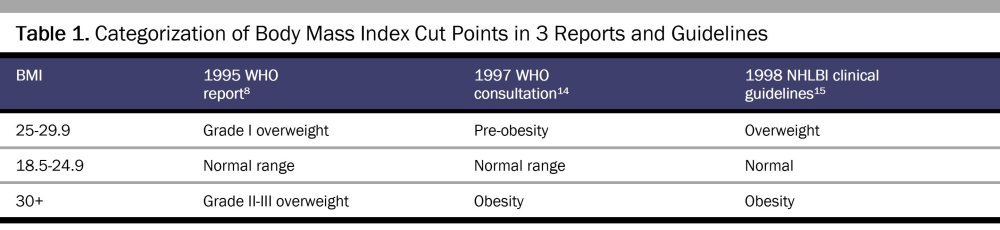

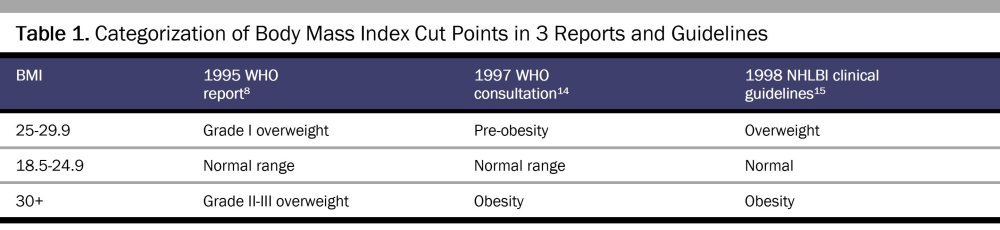

As our knowledge about weight and health advances, the criteria used to determine weight classifications have also changed. However, this shift has led to a significant number of people being labeled as above-normal weight, which raises important questions about the impact of such classifications on our perceptions of body size, public health initiatives, and individual well-being.

Maintaining overall health should always be a priority, regardless of body size or weight. This involves adopting a balanced diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and taking care of mental and emotional well-being. Similarly, one can focus on non-scale victories, such as improved energy levels, increased strength and fitness, better sleep quality, and improved overall well-being.

Weight loss is often portrayed as the primary solution to obesity. However, the Health at Every Size movement promotes the idea that health and well-being can be achieved at any size. Research has shown that long-term weight loss maintenance is challenging and often associated with weight cycling and negative health outcomes. Some studies have suggested that yo-yo dieting may be linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and other metabolic disorders.

According to data from the CDC's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), more than 70% of adults in the U.S. are classified as overweight or obese. Classifying most of the population as having above-normal weight can have various consequences, particularly regarding societal perceptions, public health policies, and individual well-being.

Below are some reasons why people should not be casually classified as overweight or obese:

1. Stigmatization and discrimination: Labeling a large portion of the population as abnormal, pathological, or deviant based on weight classification can lead to stigmatization and discrimination. This can result in negative social attitudes, bias, and unfair treatment towards individuals who are classified as above normal weight. Such stigma can affect various aspects of life, including employment, education, healthcare, and interpersonal relationships.

2. Body image and self-esteem issues: The classification of a significant portion of the population as above normal weight can contribute to negative body image and self-esteem issues. People may internalize societal expectations and experience feelings of shame, guilt, or dissatisfaction with their bodies, which can have a detrimental impact on mental health and well-being.

3. Psychological and emotional effects: Weight-based stigma and negative societal perceptions can contribute to increased psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and disordered eating behaviors. It can also lead to social isolation, poor body image, and low self-confidence. Given the health consequences of loneliness, social isolation kills more people than obesity.

4. Health implications: While BMI is a widely used measure, it has limitations in accurately assessing an individual's health status. Classifying individuals solely based on BMI can overlook important factors such as body composition, fitness level, and overall health. It may lead to misclassification of individuals who have a higher muscle mass or individuals with a healthy metabolic profile but fall above the defined BMI threshold.

5. Focus on weight rather than overall health: Placing excessive emphasis on weight classification may shift the focus away from overall health and well-being. It can lead to a narrow perspective that prioritizes weight loss as the primary goal, rather than promoting holistic health behaviors such as balanced nutrition, physical activity, and mental well-being.

It is important to approach discussions about weight and health with sensitivity, recognizing the complexity and diversity of factors that contribute to individual health and well-being. Health should be viewed as a multidimensional concept that goes beyond simplistic classifications based solely on body weight or BMI.

The NHANES studies shed light on important factors often overlooked by medical practitioners. They have investigated the impact of the neighborhood environment on obesity, revealing noteworthy findings. For instance, residing in neighborhoods with limited access to healthy food options (known as food deserts) or with a high concentration of fast-food restaurants has been linked to a heightened risk of obesity. These findings underscore the influence of the built environment and neighborhood characteristics on obesity rates.

Moreover, NHANES studies consistently demonstrate a correlation between socioeconomic factors and obesity. Individuals with higher incomes tend to exhibit lower obesity rates compared to those with lower incomes. Additionally, education level has been found to be associated with obesity, with higher levels of education linked to lower obesity rates. These findings emphasize the intricate interplay between socioeconomic factors and the risk of obesity.

Similarly, chronic anxiety and stress can trigger the release of stress hormones like cortisol. Elevated levels of cortisol over time can lead to hormonal dysregulation, which may influence appetite, food cravings, and fat storage. Cortisol can increase hunger, particularly for high-calorie and carbohydrate-rich foods, and promote the deposition of fat in the abdominal region, contributing to weight gain and obesity.

----------------

More info:

weightandhealthcare.substack.com

weightandhealthcare.substack.com

"Self-compassionate people engage in more health-promoting behaviours, particularly stress management behaviours. Self-compassion interventions may be appropriate for promoting health behaviours, particularly group-based interventions which potentially minimise feelings of isolation."

"If people are worried about their weight and want to check their risk of diabetes or heart disease, they should see a doctor to get the appropriate tests and go over the many factors affecting their health — all the information, experts agree, a BMI number can't provide."

“If you carry fat in your hips and your legs, your thighs and your rear end, that’s actually not only not bad, it’s good.”

www.sciencedirect.com

www.sciencedirect.com

"The health at every size approach enabled participants to maintain long-term behavior change; the diet approach did not. Encouraging size acceptance, reduction in dieting behavior, and heightened awareness and response to body signals resulted in improved health risk indicators for obese women."

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

"In order to enhance the overall benefit from weight-neutral approaches, these findings underscore the need to incorporate more innovative and direct methods to reduce internalized weight stigma for women with high BMI."

journalofethics.ama-assn.org

journalofethics.ama-assn.org

...Dramatic statements about the health risks of obesity are common today...Such assertions are a recent development. According to the Institute of Medicine, “Prior to the late 20th century, overweight and obesity were not considered a population wide health risk.” Body weight was often considered as more of a cosmetic and social issue than an important medical concern. A 1969 study found that patients and physicians did not view body weight and weight loss as salient medical problems and considered deviations from weight standards to be almost meaningless. Prior to 2004, the National Coverage Determinations Manual stated bluntly that “obesity itself cannot be considered an illness,” and treatment for obesity was not covered by Medicare. The costs of weight loss as a treatment for obesity were not allowed as a medical deduction for tax purposes until 2002. Until the 2010s, in most doctor visits, BMI was not calculated...

This article argues that the ensuing focus on BMI categories and on weight loss have created a narrative that is advantageous to the billion-dollar weight loss industry but has yielded little in the way of long-term health benefits and can exacerbate weight-related discrimination and stigmatization...

...The change in terminology from overweight to obese was medically and socially significant. When the American Medical Association decided in 2013 to classify obesity as a disease, it made no distinction between obesity defined as excess fat harmful to health and obesity defined as a BMI of 30 or above. There is no clearly accepted level of body fat, however, that would represent a diagnosis of obesity. Scientific organizations routinely explain that the degree of body fat that is (or may be) harmful varies by age, sex, fat distribution, and multiple other factors. In the absence of any clear definition of obesity in terms of body fat, a BMI of 30 or above is used as a cut point, but no justification has been provided for that number. The definition of "normal" weight as a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is also problematic and has no obvious justification. In almost all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, over half the population is, on this definition, above normal weight and thus in some way abnormal, pathological, or deviant. Such classifications invite stereotypes.

...BMI is not a good measure of fat mass, and fat mass itself may not be a good indicator of health. Some studies have found that low muscle mass is more of a health risk than high fat mass. Bosy-Westphal and Müller suggest that obesity should not even be considered a question of body fat per se but should be addressed in terms of body composition and that the use of both BMI and body fat percentage in assessing obesity-related health risk should be avoided. They call for a new approach focused on fat-free mass instead and point out that, at older ages, a higher BMI may indicate more adequate fat-free mass. Another new paradigm has been suggested according to which overweight and moderate obesity are beneficial for patients with a broad spectrum of chronic diseases. Physical activity and fitness may be more important for health than adiposity is. It is time to look beyond the arbitrary and questionable BMI categories and evaluate other approaches to promote health and well-being.

"We uncovered no clear relationship between weight loss and health outcomes related to hypertension, diabetes, or cholesterol,

calling into questions whether weight change per se had any causal role in the effects of the diets. Increased exercise, healthier

eating, engagement with health care system and social support may have played a role instead." ~ Tomiyama, Ahlstrom and Mann

"We envision a world where BMI does not exist." ~ The Association for Size Diversity and Health

"Some of the health effects of the obesity epidemic are related to the way we see our bodies." ~ Muennig et al

"You cannot eat your way into T2D [type 2 diabetes]." ~ HAES Health Sheets

"A future without fat is a dystopian aspiration. And it’s one that fails to acknowledge

the essential role fat plays in our bodies and in the body politic." ~ The Conversation

As our knowledge about weight and health advances, the criteria used to determine weight classifications have also changed. However, this shift has led to a significant number of people being labeled as above-normal weight, which raises important questions about the impact of such classifications on our perceptions of body size, public health initiatives, and individual well-being.

Maintaining overall health should always be a priority, regardless of body size or weight. This involves adopting a balanced diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and taking care of mental and emotional well-being. Similarly, one can focus on non-scale victories, such as improved energy levels, increased strength and fitness, better sleep quality, and improved overall well-being.

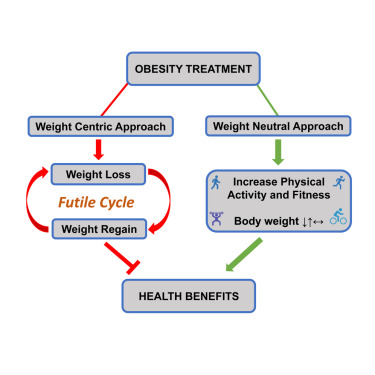

Weight loss is often portrayed as the primary solution to obesity. However, the Health at Every Size movement promotes the idea that health and well-being can be achieved at any size. Research has shown that long-term weight loss maintenance is challenging and often associated with weight cycling and negative health outcomes. Some studies have suggested that yo-yo dieting may be linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and other metabolic disorders.

According to data from the CDC's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), more than 70% of adults in the U.S. are classified as overweight or obese. Classifying most of the population as having above-normal weight can have various consequences, particularly regarding societal perceptions, public health policies, and individual well-being.

Below are some reasons why people should not be casually classified as overweight or obese:

1. Stigmatization and discrimination: Labeling a large portion of the population as abnormal, pathological, or deviant based on weight classification can lead to stigmatization and discrimination. This can result in negative social attitudes, bias, and unfair treatment towards individuals who are classified as above normal weight. Such stigma can affect various aspects of life, including employment, education, healthcare, and interpersonal relationships.

2. Body image and self-esteem issues: The classification of a significant portion of the population as above normal weight can contribute to negative body image and self-esteem issues. People may internalize societal expectations and experience feelings of shame, guilt, or dissatisfaction with their bodies, which can have a detrimental impact on mental health and well-being.

3. Psychological and emotional effects: Weight-based stigma and negative societal perceptions can contribute to increased psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and disordered eating behaviors. It can also lead to social isolation, poor body image, and low self-confidence. Given the health consequences of loneliness, social isolation kills more people than obesity.

4. Health implications: While BMI is a widely used measure, it has limitations in accurately assessing an individual's health status. Classifying individuals solely based on BMI can overlook important factors such as body composition, fitness level, and overall health. It may lead to misclassification of individuals who have a higher muscle mass or individuals with a healthy metabolic profile but fall above the defined BMI threshold.

5. Focus on weight rather than overall health: Placing excessive emphasis on weight classification may shift the focus away from overall health and well-being. It can lead to a narrow perspective that prioritizes weight loss as the primary goal, rather than promoting holistic health behaviors such as balanced nutrition, physical activity, and mental well-being.

It is important to approach discussions about weight and health with sensitivity, recognizing the complexity and diversity of factors that contribute to individual health and well-being. Health should be viewed as a multidimensional concept that goes beyond simplistic classifications based solely on body weight or BMI.

The NHANES studies shed light on important factors often overlooked by medical practitioners. They have investigated the impact of the neighborhood environment on obesity, revealing noteworthy findings. For instance, residing in neighborhoods with limited access to healthy food options (known as food deserts) or with a high concentration of fast-food restaurants has been linked to a heightened risk of obesity. These findings underscore the influence of the built environment and neighborhood characteristics on obesity rates.

Moreover, NHANES studies consistently demonstrate a correlation between socioeconomic factors and obesity. Individuals with higher incomes tend to exhibit lower obesity rates compared to those with lower incomes. Additionally, education level has been found to be associated with obesity, with higher levels of education linked to lower obesity rates. These findings emphasize the intricate interplay between socioeconomic factors and the risk of obesity.

Similarly, chronic anxiety and stress can trigger the release of stress hormones like cortisol. Elevated levels of cortisol over time can lead to hormonal dysregulation, which may influence appetite, food cravings, and fat storage. Cortisol can increase hunger, particularly for high-calorie and carbohydrate-rich foods, and promote the deposition of fat in the abdominal region, contributing to weight gain and obesity.

----------------

More info:

Weight-Neutral Health And Wegovy - Unprinted Interview

This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter! If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing! I was recently asked for an interview by a reporter who was writing about Novo Nordisk’s new weight loss drug. I sent a long answer via email and then we did a 30 minute...

Obesity treatment: Weight loss versus increasing fitness and physical activity for reducing health risks

"Self-compassionate people engage in more health-promoting behaviours, particularly stress management behaviours. Self-compassion interventions may be appropriate for promoting health behaviours, particularly group-based interventions which potentially minimise feelings of isolation."

Why top Canadian obesity experts don't use BMI

Why a top Canadian obesity expert doesn't use BMI by Nicole Ireland, CBC News Feb 23, 2020 Body mass index has been around for years, but has limited usefulness, health experts say Body mass index, or BMI, is the ratio of weight to height and has long been used as a way to classify people...

forum.psychlinks.ca

"If people are worried about their weight and want to check their risk of diabetes or heart disease, they should see a doctor to get the appropriate tests and go over the many factors affecting their health — all the information, experts agree, a BMI number can't provide."

“If you carry fat in your hips and your legs, your thighs and your rear end, that’s actually not only not bad, it’s good.”

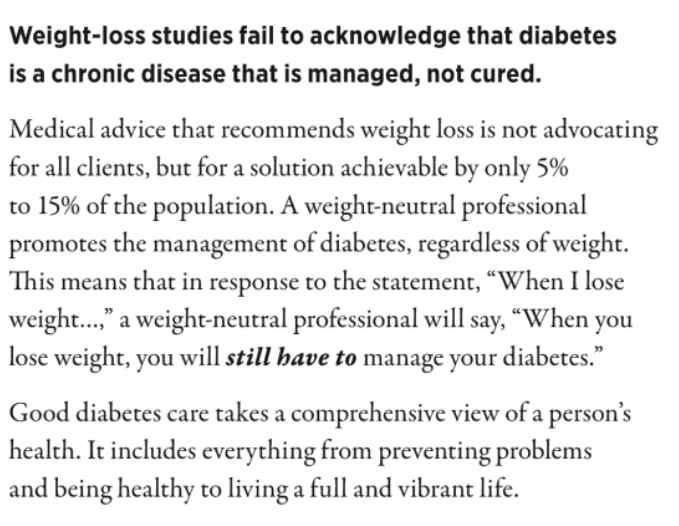

Diabetes Counseling & Education Activities: Helping clients without harping on weight

How can health professionals teach diabetes education without getting sucked into the restrictive-eating, appearance-based, weight-loss trap? Diabetes Counseling and Education Activities: Helping clients without harping on weight, is the culmination of 20 years of teaching experience by a...

www.google.com

Size Acceptance and Intuitive Eating Improve Health for Obese, Female Chronic Dieters

Examine a model that encourages health at every size as opposed to weight loss. The health at every size concept supports homeostatic regulation and e…

www.sciencedirect.com

www.sciencedirect.com

"The health at every size approach enabled participants to maintain long-term behavior change; the diet approach did not. Encouraging size acceptance, reduction in dieting behavior, and heightened awareness and response to body signals resulted in improved health risk indicators for obese women."

Internalized weight stigma moderates eating behavior outcomes in women with high BMI participating in a healthy living program - PubMed

Weight stigma is a significant socio-structural barrier to reducing health disparities and improving quality of life for higher weight individuals. The aim of this study was to examine the impact of internalized weight stigma on eating behaviors after participating in a randomized controlled...

"In order to enhance the overall benefit from weight-neutral approaches, these findings underscore the need to incorporate more innovative and direct methods to reduce internalized weight stigma for women with high BMI."

Use and Misuse of BMI Categories

Before the late 20th century, overweight and obesity were not considered population-wide health risks, but the advent of weight loss drugs in the 1990s accelerated hypermedicalization via BMI use.

...Dramatic statements about the health risks of obesity are common today...Such assertions are a recent development. According to the Institute of Medicine, “Prior to the late 20th century, overweight and obesity were not considered a population wide health risk.” Body weight was often considered as more of a cosmetic and social issue than an important medical concern. A 1969 study found that patients and physicians did not view body weight and weight loss as salient medical problems and considered deviations from weight standards to be almost meaningless. Prior to 2004, the National Coverage Determinations Manual stated bluntly that “obesity itself cannot be considered an illness,” and treatment for obesity was not covered by Medicare. The costs of weight loss as a treatment for obesity were not allowed as a medical deduction for tax purposes until 2002. Until the 2010s, in most doctor visits, BMI was not calculated...

This article argues that the ensuing focus on BMI categories and on weight loss have created a narrative that is advantageous to the billion-dollar weight loss industry but has yielded little in the way of long-term health benefits and can exacerbate weight-related discrimination and stigmatization...

...The change in terminology from overweight to obese was medically and socially significant. When the American Medical Association decided in 2013 to classify obesity as a disease, it made no distinction between obesity defined as excess fat harmful to health and obesity defined as a BMI of 30 or above. There is no clearly accepted level of body fat, however, that would represent a diagnosis of obesity. Scientific organizations routinely explain that the degree of body fat that is (or may be) harmful varies by age, sex, fat distribution, and multiple other factors. In the absence of any clear definition of obesity in terms of body fat, a BMI of 30 or above is used as a cut point, but no justification has been provided for that number. The definition of "normal" weight as a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is also problematic and has no obvious justification. In almost all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, over half the population is, on this definition, above normal weight and thus in some way abnormal, pathological, or deviant. Such classifications invite stereotypes.

...BMI is not a good measure of fat mass, and fat mass itself may not be a good indicator of health. Some studies have found that low muscle mass is more of a health risk than high fat mass. Bosy-Westphal and Müller suggest that obesity should not even be considered a question of body fat per se but should be addressed in terms of body composition and that the use of both BMI and body fat percentage in assessing obesity-related health risk should be avoided. They call for a new approach focused on fat-free mass instead and point out that, at older ages, a higher BMI may indicate more adequate fat-free mass. Another new paradigm has been suggested according to which overweight and moderate obesity are beneficial for patients with a broad spectrum of chronic diseases. Physical activity and fitness may be more important for health than adiposity is. It is time to look beyond the arbitrary and questionable BMI categories and evaluate other approaches to promote health and well-being.