David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

A fear of feeling guilty might be key to some forms of OCD

By Christian Jarrett, BPS Research Digest

February 3, 2017

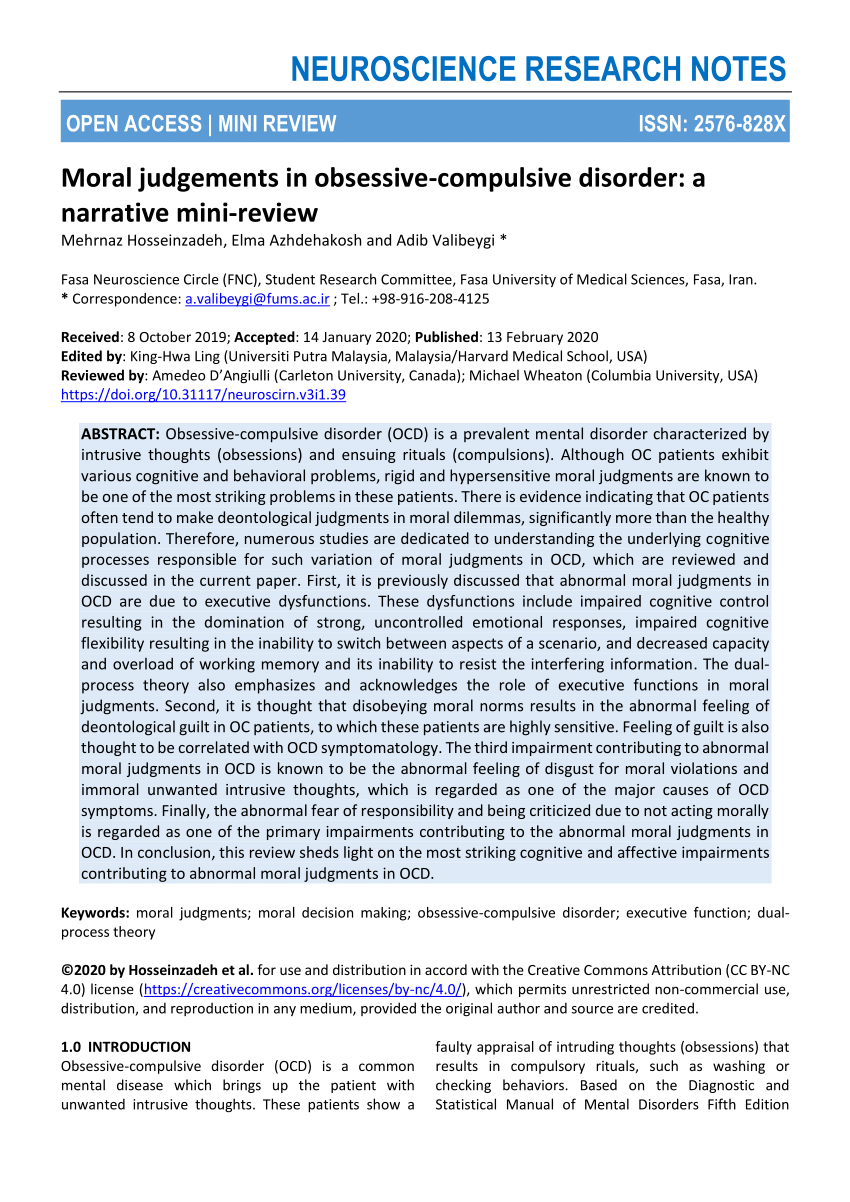

There's increasing recognition that our vulnerability to mental health problems isn't just about how much we are prone to certain emotions such as anxiety and low mood, but also how we relate to those emotions. If we find them aversive and intolerable, we're more likely to develop problems. A new study in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy applies this principle to people's experience of guilt and their vulnerability to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), helping make sense of why past research has been inconsistent on whether guilt-proneness is a risk factor for OCD or not. Gabriele Melli and his colleagues provide new evidence that the inconsistent results might be because the key factor is not how much guilt you suffer, but whether you're highly guilt-sensitive. They found that clients with OCD who said they found guilt unbearable were especially likely to have OCD symptoms related to compulsive checking, such as checking doors are locked and ovens switched off. Though preliminary, the results point to new ways to help clients with this kind of OCD.

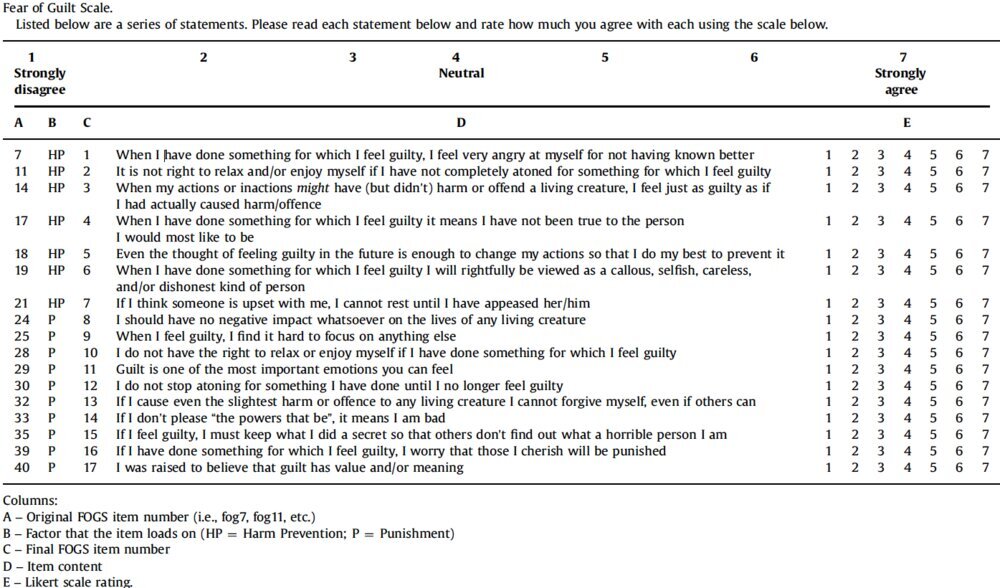

Melli and his colleagues began by creating a new scale for measuring guilt sensitivity because no such questionnaire existed. The new scale had 20 items, such as 'Guilt is one of the most intolerable feelings' and 'The idea of feeling guilty because I was careless makes me very anxious'. Nearly 500 volunteers from a local community in central Italy rated their agreement or not with these items, and they completed other questionnaires tapping their tendency to experience guilt, and their levels of OCD, depression and anxiety symptoms. The results showed that guilt sensitivity is a separate concept from guilt proneness, and that it was more strongly related to checking-related OCD symptoms than depression or general anxiety.

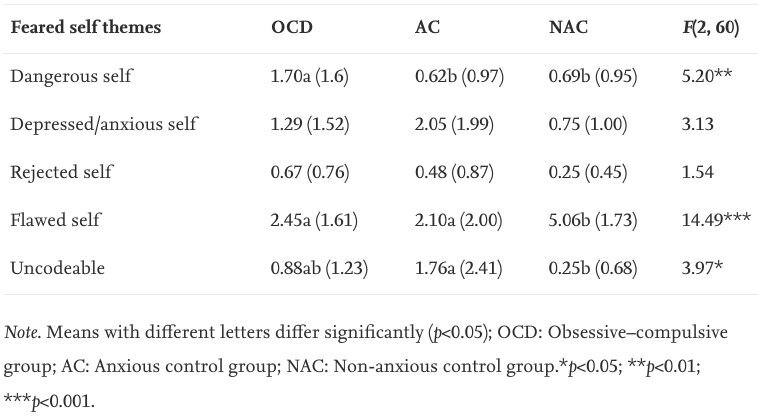

Next, the researchers asked 61 clients diagnosed with OCD and 47 others diagnosed with general anxiety disorders to complete the new guilt-sensitivity questionnaire and other scales measuring their levels of anxiety and depression. The results showed there was a strong correlation between levels of guilt sensitivity and OCD symptoms related to compulsive checking, even after controlling for different levels of general anxiety and depression and obsessive beliefs, such as an irrational sense of responsibility. Moreover, guilt-sensitivity was especially high for OCD clients whose principle symptoms related to ritualistic checking.

'Guilt sensitivity may indeed cause individuals to be vigilant and sensitive to ways in which actions or inactions could potentially cause harm, performing checking compulsions in order to avoid, prevent, or neutralise the feared feeling of guilt,' the researchers said. This could have implications for therapy, they added, suggesting that in CBT, 'cognitive restructuring should target not only inflated responsibility beliefs, but also beliefs concerning the intolerability and dangerousness of experiencing guilt.' Note, however, that the new findings were purely correlational so it's not certain that guilt sensitivity causes OCD checking symptoms or if the symptoms lead to guilt sensitivity. It may be a bit of both. Or it's even possible some unknown factors contribute to the symptoms and the guilt-sensitivity.

Reference

The role of guilt sensitivity in OCD symptom dimensions

By Christian Jarrett, BPS Research Digest

February 3, 2017

There's increasing recognition that our vulnerability to mental health problems isn't just about how much we are prone to certain emotions such as anxiety and low mood, but also how we relate to those emotions. If we find them aversive and intolerable, we're more likely to develop problems. A new study in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy applies this principle to people's experience of guilt and their vulnerability to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), helping make sense of why past research has been inconsistent on whether guilt-proneness is a risk factor for OCD or not. Gabriele Melli and his colleagues provide new evidence that the inconsistent results might be because the key factor is not how much guilt you suffer, but whether you're highly guilt-sensitive. They found that clients with OCD who said they found guilt unbearable were especially likely to have OCD symptoms related to compulsive checking, such as checking doors are locked and ovens switched off. Though preliminary, the results point to new ways to help clients with this kind of OCD.

Melli and his colleagues began by creating a new scale for measuring guilt sensitivity because no such questionnaire existed. The new scale had 20 items, such as 'Guilt is one of the most intolerable feelings' and 'The idea of feeling guilty because I was careless makes me very anxious'. Nearly 500 volunteers from a local community in central Italy rated their agreement or not with these items, and they completed other questionnaires tapping their tendency to experience guilt, and their levels of OCD, depression and anxiety symptoms. The results showed that guilt sensitivity is a separate concept from guilt proneness, and that it was more strongly related to checking-related OCD symptoms than depression or general anxiety.

Next, the researchers asked 61 clients diagnosed with OCD and 47 others diagnosed with general anxiety disorders to complete the new guilt-sensitivity questionnaire and other scales measuring their levels of anxiety and depression. The results showed there was a strong correlation between levels of guilt sensitivity and OCD symptoms related to compulsive checking, even after controlling for different levels of general anxiety and depression and obsessive beliefs, such as an irrational sense of responsibility. Moreover, guilt-sensitivity was especially high for OCD clients whose principle symptoms related to ritualistic checking.

'Guilt sensitivity may indeed cause individuals to be vigilant and sensitive to ways in which actions or inactions could potentially cause harm, performing checking compulsions in order to avoid, prevent, or neutralise the feared feeling of guilt,' the researchers said. This could have implications for therapy, they added, suggesting that in CBT, 'cognitive restructuring should target not only inflated responsibility beliefs, but also beliefs concerning the intolerability and dangerousness of experiencing guilt.' Note, however, that the new findings were purely correlational so it's not certain that guilt sensitivity causes OCD checking symptoms or if the symptoms lead to guilt sensitivity. It may be a bit of both. Or it's even possible some unknown factors contribute to the symptoms and the guilt-sensitivity.

Reference

The role of guilt sensitivity in OCD symptom dimensions

Last edited by a moderator: