An excerpt from chapter 2  of Mind and Emotions: A Universal Treatment for Emotional Disorders (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook):

of Mind and Emotions: A Universal Treatment for Emotional Disorders (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook):

How Emotional Problems Arise

Emotional problems are often blamed on stress, trauma, early upbringing, interpersonal conflicts, hormones, and genetics. But surprisingly, research shows that another factor is much more responsible for emotional disorders: our coping behaviors (Hayes 2005). We each learn to deal with the stress of life using a repertoire of coping strategies designed to reduce pain. The trouble is, some coping strategies work better than others, and some are absolutely catastrophic in terms of their long-term impact on well-being.

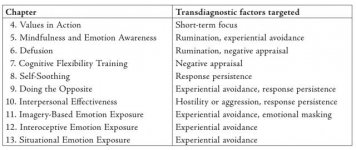

There are seven maladaptive coping strategies that drive most of our emotional distress and turn painful moments into chronic disorders. These coping strategies are called transdiagnostic factors because they are the underlying cause of symptoms across many diagnostic categories: anxiety, depression, chronic anger, borderline personality disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder, to name a few. Let?s take a look at the transdiagnostic factors, or maladaptive coping strate- gies, that lie at the root of chronic emotional pain.

Experiential avoidance. People who use this strategy automatically try to avoid painful emotions and thoughts. As soon as they feel something uncomfortable, they try to suppress, numb, or push away the experience. They attempt to put a lid on things so the pain is somehow muted. This coping strategy often backfires because avoidance not only fails to suppress painful feelings, it also makes the pain worse. An example is Harold, who withdrew socially and began drinking in an effort to avoid the sadness of losing his job. But his sadness just turned to depression as he sank into alcoholism and isolation.

Rumination. In this strategy, people use obsessive thoughts to blunt the fear of uncertainty, and use judgments in the hope of forcing themselves or others to do better. In the form of worry, rumination tries to prepare you for every bad thing that might happen. In the form of good-bad evaluations, it tries to perfect a flawed self and a flawed world. But these efforts never work. Ultimately, rumination keeps you focused on what?s bothering you, so its net effect is that you feel more anxious, more angry, or a greater sense of loss and disappointment.

Emotional masking. The aim of this coping strategy is to make sure no one ever sees your pain. It arises from a fear that if others saw your emotions, they might be contemptuous or judge you as weak, foolish, or crazy. So the mask must stay on and the feelings that burn in you must stay hidden. The price for this maladaptive strategy is that the real you remains invisible, lost in the effort to look good. You can?t show what you need or feel, so you remain helpless and possibly unfulfilled in your relationships. No one knows what hurts or what needs to change.

Short-term focus. The motto of this coping strategy is ?Why do it right when I can do it now?? When faced with emotional pain, many people focus on what can give them relief in the moment. They want to stop or suppress the emotion and will do whatever it will take to build a wall between themselves and their feelings. But while short-term focus may provide a brief moment when the pain diminishes, in an hour or a day or a week it?s back?and it?s worse than ever. That?s because short-term relief strategies often harm people in the long run. For example, drugs or alcohol can numb the pain in the moment but create long-term job, relationship, and health problems that eclipse the original distress. Another example is avoiding an upcoming social event because it makes you anxious. The short-term solution of avoidance temporarily reduces anxiety, but in the long term each choice to avoid increases the level of social fear, while also leading to isolation and risk of depression.

Response persistence. In this transdiagnostic factor, you continue responding to similar situations in the same way, even when it doesn?t work. Sometimes this happens because you?re afraid to try other responses. Or maybe you have inner rules that prevent you from seeking a new solution. Either way, the result is that you become inflexible and always cope with problems the same old way. You?ve heard the adage that every problem looks like a nail when all you have is a hammer. Likewise, every conflict turns into a fight when all you know how to do is get angry, and every little mistake turns into a catastrophe when all you know how to do is brood and castigate yourself about it.

Hostility or aggression. This coping solution helps mask stress, fear, loss, guilt, shame, confusion, a sense that you?re wrong or bad, the feeling of being engulfed or overwhelmed, and a host of other painful emotions. Anger is a big lid that covers a lot of pain and keeps it out of your awareness. This solution is often effective in the short term, but research shows that the more you use anger to cope, the angrier you get (Tavris 1989). Hostility begets even more hostility in a vicious circle that poisons lives.

Negative appraisal. This coping response uses negative evaluations or judgments to help you prepare for failure and bad outcomes, control others, or beat yourself into being a better person. If you use this strategy habitually, you?ll tend to expect things to go wrong and to focus on things that actually are wrong. This attention to the negative may seem to protect you from painful surprises, but you?ll end up feeling more angry, anxious, and depressed because you filter out most positive experiences. An example is a man who stumbled in a speech at his daughter?s wedding and could hardly think about anything else for the rest of the night. Meanwhile, he was missing the joy he could have been feeling.

of Mind and Emotions: A Universal Treatment for Emotional Disorders (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook):

of Mind and Emotions: A Universal Treatment for Emotional Disorders (New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook):How Emotional Problems Arise

Emotional problems are often blamed on stress, trauma, early upbringing, interpersonal conflicts, hormones, and genetics. But surprisingly, research shows that another factor is much more responsible for emotional disorders: our coping behaviors (Hayes 2005). We each learn to deal with the stress of life using a repertoire of coping strategies designed to reduce pain. The trouble is, some coping strategies work better than others, and some are absolutely catastrophic in terms of their long-term impact on well-being.

There are seven maladaptive coping strategies that drive most of our emotional distress and turn painful moments into chronic disorders. These coping strategies are called transdiagnostic factors because they are the underlying cause of symptoms across many diagnostic categories: anxiety, depression, chronic anger, borderline personality disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder, to name a few. Let?s take a look at the transdiagnostic factors, or maladaptive coping strate- gies, that lie at the root of chronic emotional pain.

Experiential avoidance. People who use this strategy automatically try to avoid painful emotions and thoughts. As soon as they feel something uncomfortable, they try to suppress, numb, or push away the experience. They attempt to put a lid on things so the pain is somehow muted. This coping strategy often backfires because avoidance not only fails to suppress painful feelings, it also makes the pain worse. An example is Harold, who withdrew socially and began drinking in an effort to avoid the sadness of losing his job. But his sadness just turned to depression as he sank into alcoholism and isolation.

Rumination. In this strategy, people use obsessive thoughts to blunt the fear of uncertainty, and use judgments in the hope of forcing themselves or others to do better. In the form of worry, rumination tries to prepare you for every bad thing that might happen. In the form of good-bad evaluations, it tries to perfect a flawed self and a flawed world. But these efforts never work. Ultimately, rumination keeps you focused on what?s bothering you, so its net effect is that you feel more anxious, more angry, or a greater sense of loss and disappointment.

Emotional masking. The aim of this coping strategy is to make sure no one ever sees your pain. It arises from a fear that if others saw your emotions, they might be contemptuous or judge you as weak, foolish, or crazy. So the mask must stay on and the feelings that burn in you must stay hidden. The price for this maladaptive strategy is that the real you remains invisible, lost in the effort to look good. You can?t show what you need or feel, so you remain helpless and possibly unfulfilled in your relationships. No one knows what hurts or what needs to change.

Short-term focus. The motto of this coping strategy is ?Why do it right when I can do it now?? When faced with emotional pain, many people focus on what can give them relief in the moment. They want to stop or suppress the emotion and will do whatever it will take to build a wall between themselves and their feelings. But while short-term focus may provide a brief moment when the pain diminishes, in an hour or a day or a week it?s back?and it?s worse than ever. That?s because short-term relief strategies often harm people in the long run. For example, drugs or alcohol can numb the pain in the moment but create long-term job, relationship, and health problems that eclipse the original distress. Another example is avoiding an upcoming social event because it makes you anxious. The short-term solution of avoidance temporarily reduces anxiety, but in the long term each choice to avoid increases the level of social fear, while also leading to isolation and risk of depression.

Response persistence. In this transdiagnostic factor, you continue responding to similar situations in the same way, even when it doesn?t work. Sometimes this happens because you?re afraid to try other responses. Or maybe you have inner rules that prevent you from seeking a new solution. Either way, the result is that you become inflexible and always cope with problems the same old way. You?ve heard the adage that every problem looks like a nail when all you have is a hammer. Likewise, every conflict turns into a fight when all you know how to do is get angry, and every little mistake turns into a catastrophe when all you know how to do is brood and castigate yourself about it.

Hostility or aggression. This coping solution helps mask stress, fear, loss, guilt, shame, confusion, a sense that you?re wrong or bad, the feeling of being engulfed or overwhelmed, and a host of other painful emotions. Anger is a big lid that covers a lot of pain and keeps it out of your awareness. This solution is often effective in the short term, but research shows that the more you use anger to cope, the angrier you get (Tavris 1989). Hostility begets even more hostility in a vicious circle that poisons lives.

Negative appraisal. This coping response uses negative evaluations or judgments to help you prepare for failure and bad outcomes, control others, or beat yourself into being a better person. If you use this strategy habitually, you?ll tend to expect things to go wrong and to focus on things that actually are wrong. This attention to the negative may seem to protect you from painful surprises, but you?ll end up feeling more angry, anxious, and depressed because you filter out most positive experiences. An example is a man who stumbled in a speech at his daughter?s wedding and could hardly think about anything else for the rest of the night. Meanwhile, he was missing the joy he could have been feeling.