David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

Is Your Doctor Burned Out?

by Peter Jaret, Berkeley Wellness

February 23, 2018

A family physician and palliative care expert at the University of Rochester Medical Center, Ronald Epstein, MD, has long warned about the growing phenomenon of physician burnout. In 2000, Epstein co-founded the Mindful Practice program, which offers workshops to help doctors handle the increasing pressures of the profession. He is also author of the book Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity (Scribner, 2017). Epstein spoke with us about why physician burnout is a growing problem, and why we should all be concerned.

What are the signs and symptoms of physician burnout?

There are various definitions of burnout, but one of the most widely used has three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (treating other people as objects), and feeling inadequate and powerless. When doctors become burned out, they begin to lose their ability to attend to patients, to listen, to diagnose and treat them effectively. Many end up leaving the profession prematurely, which puts strain on the health care system.

How serious is the problem?

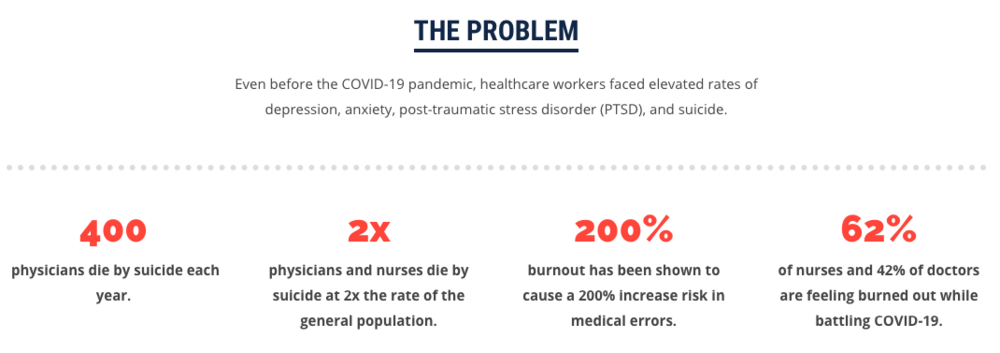

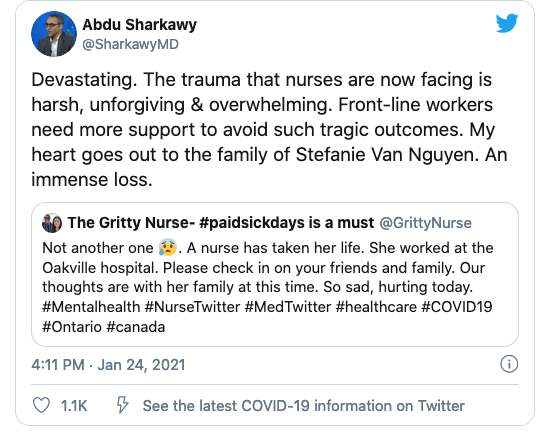

Very serious. According to one of the most common measures used, called the Maslach Burnout Inventory, 56 percent of physicians are experiencing burnout. There are other measures that estimate a lower percentage, around 30 percent. But even that’s a very large number. By any measure, burnout affects a sizeable portion of the medical community. And it’s not just doctors. It’s nurses and other health care professionals as well. And it’s getting worse. Between 2011 and 2014, burnout measured by the Maslach Inventory increased by 11 percent. Among the specialties at highest risk are emergency physicians, OB/GYNs, family doctors, and internal medicine physicians. But burnout is a serious problem in almost all areas of medicine.

And it’s not just doctors. It’s nurses and other health care professionals as well. And it’s getting worse. Between 2011 and 2014, burnout measured by the Maslach Inventory increased by 11 percent. Among the specialties at highest risk are emergency physicians, OB/GYNs, family doctors, and internal medicine physicians. But burnout is a serious problem in almost all areas of medicine.

Why is burnout on the rise?

There are several reasons. First, the administrative burdens on doctors have increased significantly. There are more for forms to fill out, more boxes to check, and a deluge of digital information. All of that means extra work that limits the amount of time doctors can spend with patients. The burden is compounded by the fact that we have a very dysfunctional electronic medical record system that not only demands too much of a physician’s time and attention but also doesn’t provide the benefits it was supposed to provide.

Another factor is the rise of health quality metrics. Measuring quality of care is important, of course. But if doctors pay too much attention to what’s being measured, they may ignore things that are most relevant to patients. Doctors increasingly find themselves having to answer to two masters — administrators who are measuring specific productivity and quality metrics, and patients, who often have ill-defined human needs that don’t fit into the metrics. All of these things demand more and more of a doctor’s time and attention, and keep them from doing what they do best, caring for patients.

You offer workshops to help physicians deal with burnout. What do you hear from them?

Most doctors go into medicine because they enjoy the challenges and they want to help people. Increasingly they’re finding that their day-to-day work is further and further from what they went into medicine for. They are overwhelmed by too much information coming at them that they don’t have time to fully process. Physicians have always had limited time. But because of the growing administrative demands, they have less and less time to relate to patients. Too often, patients feel as if doctors are treating them as just another number. Doctors feel like factory workers meeting a quota rather than engaging in the deeply important human enterprise of medicine.

What are the consequences in terms of medical diagnosis and treatment?

When doctors experience burnout, they are more likely to come to what we call “premature closure.” They gather data about the patient, come up with their best hunch, and that’s the end of it. They lose their ability to keep an open mind, to consider other possibilities. And that’s not the way to practice medicine. Medicine is an art. You have to keep an open mind. Your initial impression may not be correct.

Some doctors begin to shut down. It’s a self-protective mechanism, but it ends up making them feel even more isolated and exacerbates the problem. When physicians become burned out, they lose their sense of curiosity. Patients become widgets, things that need to be processed as opposed to human beings to relate to. That impoverishes the relationship on both sides, and it jeopardizes a patient’s health and safety.

What’s being done within the profession to address burnout?

There is a growing awareness that burnout is a serious problem, which is an essential first step. There are mandates from more and more professional organizations and medical schools to address burnout in the health care workforce in a meaningful way. Some organizations have been really visionary in their approach, finding the points of pain and stress in the delivery of health care and addressing them directly, by improving the electronic health record systems, for example, and easing administrative burdens on health care professionals. Many institutions have begun to offer workshops in mindfulness, conflict resolution, and stress management. Some now use the well-being of health care professionals as a quality metric. One health care organization, for example, has tied its CEO’s bonus to the well-being of the workforce.

Is there anything we as patients can do?

Patients aren’t responsible for physician burnout, of course, but they can do a lot to help doctors provide the best care. When you come in for an appointment, be prepared. Have a clear sense of what’s motivating your visit and what you hope to get out of it. Most patients come in with a list of several complaints or concerns. They have a rash. They’ve been getting headaches. Oh yes, and they’ve been having chest pain. For a variety of reasons, patients tend to bring up the thing they’re most concerned about last, often just at the end of a visit. Talk to your doctor first about what worries you the most. Be explicit. Tell your doctor why you’re so concerned about a specific symptom. That way, your doctor can give it his or her full attention.

If you have questions or concerns about a treatment or suggestion your doctor offers, say so. We know that between one-quarter and one-third of patients don’t take prescriptions or follow the advice they’ve been given. If you’ve tried a treatment before and it didn’t work, your doctor should know that. If you’re worried about the side effects because of something a neighbor said or you’ve read online, bring it up with your doctor.

And if you have concerns that can’t be covered in a single visit, be willing to schedule another appointment. You can’t go in with a list of 20 things and expect your doctor to cover them in a 20-minute appointment.

Ideally, your relationship with your doctor should be a relationship of sharing — sharing information, sharing thought processes, sharing decisions. I use the term “shared minds.” You and your doctor may not necessarily agree on everything. But you understand each other and speak the same language. Fostering a relationship that’s open and flexible, a relationship of mutual respect, is one of the best things we can do to counter burnout and restore the essential aspect of human caring to medical practice.

by Peter Jaret, Berkeley Wellness

February 23, 2018

A family physician and palliative care expert at the University of Rochester Medical Center, Ronald Epstein, MD, has long warned about the growing phenomenon of physician burnout. In 2000, Epstein co-founded the Mindful Practice program, which offers workshops to help doctors handle the increasing pressures of the profession. He is also author of the book Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity (Scribner, 2017). Epstein spoke with us about why physician burnout is a growing problem, and why we should all be concerned.

What are the signs and symptoms of physician burnout?

There are various definitions of burnout, but one of the most widely used has three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (treating other people as objects), and feeling inadequate and powerless. When doctors become burned out, they begin to lose their ability to attend to patients, to listen, to diagnose and treat them effectively. Many end up leaving the profession prematurely, which puts strain on the health care system.

How serious is the problem?

Very serious. According to one of the most common measures used, called the Maslach Burnout Inventory, 56 percent of physicians are experiencing burnout. There are other measures that estimate a lower percentage, around 30 percent. But even that’s a very large number. By any measure, burnout affects a sizeable portion of the medical community.

And it’s not just doctors. It’s nurses and other health care professionals as well. And it’s getting worse. Between 2011 and 2014, burnout measured by the Maslach Inventory increased by 11 percent. Among the specialties at highest risk are emergency physicians, OB/GYNs, family doctors, and internal medicine physicians. But burnout is a serious problem in almost all areas of medicine.

And it’s not just doctors. It’s nurses and other health care professionals as well. And it’s getting worse. Between 2011 and 2014, burnout measured by the Maslach Inventory increased by 11 percent. Among the specialties at highest risk are emergency physicians, OB/GYNs, family doctors, and internal medicine physicians. But burnout is a serious problem in almost all areas of medicine. Why is burnout on the rise?

There are several reasons. First, the administrative burdens on doctors have increased significantly. There are more for forms to fill out, more boxes to check, and a deluge of digital information. All of that means extra work that limits the amount of time doctors can spend with patients. The burden is compounded by the fact that we have a very dysfunctional electronic medical record system that not only demands too much of a physician’s time and attention but also doesn’t provide the benefits it was supposed to provide.

Another factor is the rise of health quality metrics. Measuring quality of care is important, of course. But if doctors pay too much attention to what’s being measured, they may ignore things that are most relevant to patients. Doctors increasingly find themselves having to answer to two masters — administrators who are measuring specific productivity and quality metrics, and patients, who often have ill-defined human needs that don’t fit into the metrics. All of these things demand more and more of a doctor’s time and attention, and keep them from doing what they do best, caring for patients.

You offer workshops to help physicians deal with burnout. What do you hear from them?

Most doctors go into medicine because they enjoy the challenges and they want to help people. Increasingly they’re finding that their day-to-day work is further and further from what they went into medicine for. They are overwhelmed by too much information coming at them that they don’t have time to fully process. Physicians have always had limited time. But because of the growing administrative demands, they have less and less time to relate to patients. Too often, patients feel as if doctors are treating them as just another number. Doctors feel like factory workers meeting a quota rather than engaging in the deeply important human enterprise of medicine.

What are the consequences in terms of medical diagnosis and treatment?

When doctors experience burnout, they are more likely to come to what we call “premature closure.” They gather data about the patient, come up with their best hunch, and that’s the end of it. They lose their ability to keep an open mind, to consider other possibilities. And that’s not the way to practice medicine. Medicine is an art. You have to keep an open mind. Your initial impression may not be correct.

Some doctors begin to shut down. It’s a self-protective mechanism, but it ends up making them feel even more isolated and exacerbates the problem. When physicians become burned out, they lose their sense of curiosity. Patients become widgets, things that need to be processed as opposed to human beings to relate to. That impoverishes the relationship on both sides, and it jeopardizes a patient’s health and safety.

What’s being done within the profession to address burnout?

There is a growing awareness that burnout is a serious problem, which is an essential first step. There are mandates from more and more professional organizations and medical schools to address burnout in the health care workforce in a meaningful way. Some organizations have been really visionary in their approach, finding the points of pain and stress in the delivery of health care and addressing them directly, by improving the electronic health record systems, for example, and easing administrative burdens on health care professionals. Many institutions have begun to offer workshops in mindfulness, conflict resolution, and stress management. Some now use the well-being of health care professionals as a quality metric. One health care organization, for example, has tied its CEO’s bonus to the well-being of the workforce.

Is there anything we as patients can do?

Patients aren’t responsible for physician burnout, of course, but they can do a lot to help doctors provide the best care. When you come in for an appointment, be prepared. Have a clear sense of what’s motivating your visit and what you hope to get out of it. Most patients come in with a list of several complaints or concerns. They have a rash. They’ve been getting headaches. Oh yes, and they’ve been having chest pain. For a variety of reasons, patients tend to bring up the thing they’re most concerned about last, often just at the end of a visit. Talk to your doctor first about what worries you the most. Be explicit. Tell your doctor why you’re so concerned about a specific symptom. That way, your doctor can give it his or her full attention.

If you have questions or concerns about a treatment or suggestion your doctor offers, say so. We know that between one-quarter and one-third of patients don’t take prescriptions or follow the advice they’ve been given. If you’ve tried a treatment before and it didn’t work, your doctor should know that. If you’re worried about the side effects because of something a neighbor said or you’ve read online, bring it up with your doctor.

And if you have concerns that can’t be covered in a single visit, be willing to schedule another appointment. You can’t go in with a list of 20 things and expect your doctor to cover them in a 20-minute appointment.

Ideally, your relationship with your doctor should be a relationship of sharing — sharing information, sharing thought processes, sharing decisions. I use the term “shared minds.” You and your doctor may not necessarily agree on everything. But you understand each other and speak the same language. Fostering a relationship that’s open and flexible, a relationship of mutual respect, is one of the best things we can do to counter burnout and restore the essential aspect of human caring to medical practice.