New drug for migraines

USA Today

November 5, 2008

Headaches distract. Migraines can debilitate. Nearly 30 million Americans suffer from the throbbing pain, costing employers about $13 billion a year from missed workdays and impaired work function, according to research reported in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

"You can be out for three days - lie there and not move, feel nauseous but not throw up - it's incapacitating," says Jeanne Safer, 61, of New York, a psychotherapist who has had regular migraines for about a decade.

But new treatments in the pipeline may help control the pain. Some "exciting" new drugs are coming into the headache field, says Alan Rapoport, a UCLA professor of neurology who has studied headaches for 35 years.

Scientists still haven't agreed on a single cause of migraines, although genetic and hormonal factors and some environmental triggers often play a part.

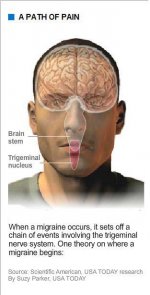

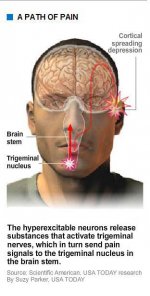

But wherever a migraine starts, whether with malfunctioning nerve cells deep in the brain stem or hyperexcited neurons in the cerebral cortex, it sets off something called the trigeminal nerve system, which carries sensory information from the face, head and meninges (membranes covering the brain and spinal cord) to the brain stem.

During a migraine, the trigeminal nerve releases a peptide called CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide), which causes dilation of blood vessels and increased pain signaling. A drug that would prevent the peptide from activating the neurons is in final trials - Merck's telcagepant. Its latest study showed about 55 percent of patients had marked pain relief, and 23 percent were pain-free after two hours, significantly better than placebo patients. Merck plans to apply for Food and Drug Administration approval for telcagepant next year. Other companies are starting trials on similar drugs.

Interest among migraine specialists stems from evidence that these drugs are at least as effective as triptans, the most commonly prescribed class of migraine drug, writes Stephen Silberstein in the October issue of The Lancet.

Triptans were considered a major breakthrough when they arrived about 15 years ago. But unlike triptans, the new drugs don't constrict vessels, so they may be safer for patients with high blood pressure, high cholesterol and a variety of vascular diseases.

The heart warnings on triptans make some patients nervous, including Safer. But because she has about 15 headaches a month, she's settled on taking her triptan, Maxalt, in addition to Botox injections every 2 months and, if the pain is unbearable and she has used up her medication, shots of lidocaine, an anesthetic. Patients who received Botox had fewer days with headaches compared with those who got dummy injections, according to two studies funded by drugmaker Allergan.

See The Path Of Pain illustrated in the four thumbnail pictures below. Click on each thumbnail for an enlarged view

USA Today

November 5, 2008

Headaches distract. Migraines can debilitate. Nearly 30 million Americans suffer from the throbbing pain, costing employers about $13 billion a year from missed workdays and impaired work function, according to research reported in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

"You can be out for three days - lie there and not move, feel nauseous but not throw up - it's incapacitating," says Jeanne Safer, 61, of New York, a psychotherapist who has had regular migraines for about a decade.

But new treatments in the pipeline may help control the pain. Some "exciting" new drugs are coming into the headache field, says Alan Rapoport, a UCLA professor of neurology who has studied headaches for 35 years.

Scientists still haven't agreed on a single cause of migraines, although genetic and hormonal factors and some environmental triggers often play a part.

But wherever a migraine starts, whether with malfunctioning nerve cells deep in the brain stem or hyperexcited neurons in the cerebral cortex, it sets off something called the trigeminal nerve system, which carries sensory information from the face, head and meninges (membranes covering the brain and spinal cord) to the brain stem.

During a migraine, the trigeminal nerve releases a peptide called CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide), which causes dilation of blood vessels and increased pain signaling. A drug that would prevent the peptide from activating the neurons is in final trials - Merck's telcagepant. Its latest study showed about 55 percent of patients had marked pain relief, and 23 percent were pain-free after two hours, significantly better than placebo patients. Merck plans to apply for Food and Drug Administration approval for telcagepant next year. Other companies are starting trials on similar drugs.

Interest among migraine specialists stems from evidence that these drugs are at least as effective as triptans, the most commonly prescribed class of migraine drug, writes Stephen Silberstein in the October issue of The Lancet.

Triptans were considered a major breakthrough when they arrived about 15 years ago. But unlike triptans, the new drugs don't constrict vessels, so they may be safer for patients with high blood pressure, high cholesterol and a variety of vascular diseases.

The heart warnings on triptans make some patients nervous, including Safer. But because she has about 15 headaches a month, she's settled on taking her triptan, Maxalt, in addition to Botox injections every 2 months and, if the pain is unbearable and she has used up her medication, shots of lidocaine, an anesthetic. Patients who received Botox had fewer days with headaches compared with those who got dummy injections, according to two studies funded by drugmaker Allergan.

See The Path Of Pain illustrated in the four thumbnail pictures below. Click on each thumbnail for an enlarged view