David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

Getting Rid of Painful Thoughts

by Brian Thompson, Ph.D.

Jul 9th 2010

Complete the following:

However, this is what many clients want when seeking psychotherapy. Instead of nursery rhyme endings, however, they want to rid themselves of painful thoughts such as, "I'm not good enough," "I'm damaged," or "I never do anything right." When asked, people often remember having had these thoughts since childhood. It may be something their parents said to them, something said to them by peers or a teacher-sometimes people don't know where they came from! And it doesn't really matter how they got there-the problem is that they stick around, pop up, and get in the way.

One thing we know about memory is that it's additive; this means that it's easy to make new associations but nearly impossible to get rid of old ones via effort. In fact, attempting to get rid of certain thoughts usually backfires, increasing the likelihood they'll show up again.

For example, for the next 3 minutes, try not to think of a white bear. Really. Give it a shot...then see what happens. Wait until you're done before you read on.

How many times did you think of a white bear? Very few people are able to go a whole three minutes without thinking of a white bear even once. Most think of it many times. Two decades of research by Harvard psychologist Daniel Wegner has shown that when we try to not think about something, we actually think about it more.

So what do we do?

We can't control what we think, but we can choose whether to buy into it or not.

Here's an exercise: picture a lemon, perhaps sliced in half. Notice how even the thought of a lemon can make your mouth water in anticipation of its sourness. This is similar to how a particular memory can make us feel shame and embarrassment all over again. Now say the word, "lemon" over and over again repeatedly for 45 seconds while noticing what happens. Really. Give it a shot...don't read on until you've done it.

Most people find that the word "lemon" dissolves into a series of meaningless sounds towards the end. It loses all qualities of its "lemon-ness." Although it may seem strange to compare a lemon to painful self-criticisms, that is all those painful self-statements are-sounds, images, stimuli.

We all have thoughts we struggle with, though sometimes we don't think of them as thoughts. Think about a way you evaluate yourself. What do you like least about yourself? What is ugliest about you? How are you most hurtful? Each of us has some thoughts like these that we struggle with. Now imagine that thought on a computer screen, as if you were sitting at the computer and it simply popped up on the screen like an advertisement. Notice how it is made up of distinct words. Those words are made out of distinct letters. Those letters are made out of distinct lines. Those lines are made out of distinct pixels. And so on. Again, give it a shot. Actually visualize it and see what it's like to see that thought as words instead of what it says it is.

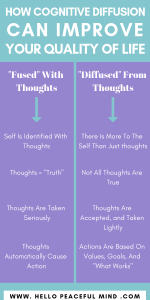

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (called ACT, spoken as in one word act), we call this process "cognitive defusion." By defusion, we mean that we no longer take our thoughts and feelings as literal "truth." When we no longer believe in our thoughts, we are free to pursue our lives in ways that our important to us now, not according to unhelpful thoughts that have been stuck in our heads for years.

Sometimes people defend those painful thoughts. They might say that they are true, or that they feel the need to at least evaluate whether they are true. In ACT, it's not important whether a thought is true or not. The main question is workability: if I buy into a thought, what kinds of actions will I take? Will following that thought take me in the direction of a life I value? Sometimes the answer is yes, but often we can become so caught up in these experiences that we aren't able to live our lives as we would like.

So, what I am saying is that struggling with a particularly painful thought is a losing battle. Even if we win momentarily, chances are it will return again. However, we can choose whether it is helpful to buy into that thought. In doing so, the thought becomes something we look "at" rather than a lens we look "through."

This is just a basic introduction to cognitive defusion and the problems that can come up when we try to control our thoughts. If you're interested in some other defusion exercises, our clinic website has some audio files with guided defusion exercises. Mindfulness is also a way to promote defusion, and we've collected have some mindfulness exercises as well. In particular, check out the Leaves on the Stream exercises.

Brian Thompson, PhD, is a psychologist resident at Portland Psychotherapy Clinic, Research, and Training Center in Portland, Oregon. In addition to conducting research, he sees clients in psychotherapy and specializes in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and other forms of trauma. Brian also co-founded a blog about research on mindfulness and acceptance called Scientific Mindfulness.

by Brian Thompson, Ph.D.

Jul 9th 2010

Complete the following:

- Twinkle, twinkle little _________.

- Mary had a little __________.

- Hickory dickory __________.

However, this is what many clients want when seeking psychotherapy. Instead of nursery rhyme endings, however, they want to rid themselves of painful thoughts such as, "I'm not good enough," "I'm damaged," or "I never do anything right." When asked, people often remember having had these thoughts since childhood. It may be something their parents said to them, something said to them by peers or a teacher-sometimes people don't know where they came from! And it doesn't really matter how they got there-the problem is that they stick around, pop up, and get in the way.

One thing we know about memory is that it's additive; this means that it's easy to make new associations but nearly impossible to get rid of old ones via effort. In fact, attempting to get rid of certain thoughts usually backfires, increasing the likelihood they'll show up again.

For example, for the next 3 minutes, try not to think of a white bear. Really. Give it a shot...then see what happens. Wait until you're done before you read on.

How many times did you think of a white bear? Very few people are able to go a whole three minutes without thinking of a white bear even once. Most think of it many times. Two decades of research by Harvard psychologist Daniel Wegner has shown that when we try to not think about something, we actually think about it more.

So what do we do?

We can't control what we think, but we can choose whether to buy into it or not.

Here's an exercise: picture a lemon, perhaps sliced in half. Notice how even the thought of a lemon can make your mouth water in anticipation of its sourness. This is similar to how a particular memory can make us feel shame and embarrassment all over again. Now say the word, "lemon" over and over again repeatedly for 45 seconds while noticing what happens. Really. Give it a shot...don't read on until you've done it.

Most people find that the word "lemon" dissolves into a series of meaningless sounds towards the end. It loses all qualities of its "lemon-ness." Although it may seem strange to compare a lemon to painful self-criticisms, that is all those painful self-statements are-sounds, images, stimuli.

We all have thoughts we struggle with, though sometimes we don't think of them as thoughts. Think about a way you evaluate yourself. What do you like least about yourself? What is ugliest about you? How are you most hurtful? Each of us has some thoughts like these that we struggle with. Now imagine that thought on a computer screen, as if you were sitting at the computer and it simply popped up on the screen like an advertisement. Notice how it is made up of distinct words. Those words are made out of distinct letters. Those letters are made out of distinct lines. Those lines are made out of distinct pixels. And so on. Again, give it a shot. Actually visualize it and see what it's like to see that thought as words instead of what it says it is.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (called ACT, spoken as in one word act), we call this process "cognitive defusion." By defusion, we mean that we no longer take our thoughts and feelings as literal "truth." When we no longer believe in our thoughts, we are free to pursue our lives in ways that our important to us now, not according to unhelpful thoughts that have been stuck in our heads for years.

Sometimes people defend those painful thoughts. They might say that they are true, or that they feel the need to at least evaluate whether they are true. In ACT, it's not important whether a thought is true or not. The main question is workability: if I buy into a thought, what kinds of actions will I take? Will following that thought take me in the direction of a life I value? Sometimes the answer is yes, but often we can become so caught up in these experiences that we aren't able to live our lives as we would like.

So, what I am saying is that struggling with a particularly painful thought is a losing battle. Even if we win momentarily, chances are it will return again. However, we can choose whether it is helpful to buy into that thought. In doing so, the thought becomes something we look "at" rather than a lens we look "through."

This is just a basic introduction to cognitive defusion and the problems that can come up when we try to control our thoughts. If you're interested in some other defusion exercises, our clinic website has some audio files with guided defusion exercises. Mindfulness is also a way to promote defusion, and we've collected have some mindfulness exercises as well. In particular, check out the Leaves on the Stream exercises.

Brian Thompson, PhD, is a psychologist resident at Portland Psychotherapy Clinic, Research, and Training Center in Portland, Oregon. In addition to conducting research, he sees clients in psychotherapy and specializes in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and other forms of trauma. Brian also co-founded a blog about research on mindfulness and acceptance called Scientific Mindfulness.