What is emptiness? Clarifying the 7th criterion for borderline personality disorder

August 2008

The present study aims to clarify the 7th DSM-IV criterion for Borderline Personality Disorder: "chronic feelings of emptiness." Emptiness has been the subject of little empirical investigation. The relationship of emptiness to boredom and other affect-states is uncertain, and patients and clinicians can find it difficult to generate verbal descriptions of emptiness. In the present study, two sets of analyses address the meaning and clinical implications of feeling empty. First, affect-states that co-occur with emptiness are identified in 45 young adults who exhibit a prominent feature of Borderline Personality Disorder (i.e., self-injury). Second, the relationship of chronic emptiness to key psychiatric variables is examined in a large nonclinical sample (n = 274). Results indicate thatemptiness is negligibly related to boredom, is closely related to feeling hopeless, lonely, and isolated, and is a robust predictor of depression and suicidal ideation (but not anxiety or suicide attempts). Findings are consistent with DSM-IV revisions regarding the 7th criterion for Borderline Personality Disorder. In addition, findings suggest that emptiness reflects pathologically low positive affect and significant psychiatric distress.

.................................

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (1993)

by Marsha Linehan

A tendency of borderline patients to inhibit, or attempt to inhibit, emotional responses may also contribute to an absence of a strong sense of identity. The numbness associated with inhibited affect is often experienced as emptiness, further contributing to an inadequate (at at times completely absent) sense of self. Similarly, if an individual's own sense of events is never "correct" or is unpredictably "correct" -- the situation in the invalidating family -- then one would expect the individual to develop an overdependence upon others. This overdependence, especially when the dependence relates to preferences, ideas, and opinions, simply exacerbates problems with identity, and a vicious cycle is once again started.

.................................

Cascades of Emotion: The Emergence of Borderline Personality Disorder from Emotional and Behavioral Dysregulation

September 2009

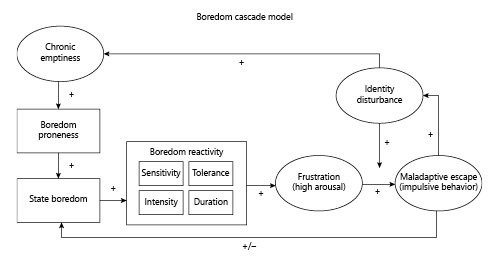

...Problems with identity may lead to maladaptive cognitions, negative views of others, or feelings of emptiness. Wilkinson-Ryan and Westen (2000) have found that two specific factors of identity disturbance, painful incoherence (feelings of distress about lacking a coherent sense of self), and lack of commitment (difficulties committing to goals or maintaining a constant set of values) are highly related to the emotion dysregulation features of BPD. So identity disturbance phenomena may be part of what contributes to emotional cascades in BPD, but more research is needed to determine why this may be and if there is a relationship between identity diffusion and rumination...

.................................

Borderline Emptiness

by Randi Kreger, co-author of Stop Walking on Eggshells

October 2011

For people with BPD, feelings of emptiness go hand-in-hand with another BPD trait, lack of identity. Not knowing who you are naturally exacerbates feelings of emptiness. Those with the disorder become chameleons, mimicking some of the attributes of people they're with to fit in. We will look at this trait in some depth later on.

Also, those with BPD usually seek emotionally intimate connections--even if it means negative emotions--to help fill this chronic feeling of emptiness. When things are calm--even in a secure relationship--they may feel empty and insecure inside, so they create a conflict in order to feel more emotional intensity and connection (although this often serves to push people away, which is the opposite of their intent).

But this emptiness keeps popping up inside, driving them to seek intimacy even from people who aren't capable of it. Some professionals believe that "cutting" behavior is associated with those with BPD trying to feel "something" in order to not feel empty, disconnected, alone and abandoned.

.................................

Who Am I? The Conundrum of Both Borderlines and Narcissists

by Randi Kreger, co-author of Stop Walking on Eggshells

November 2011

In a previous post, I explained that people borderline personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder both have an awful sense of emptiness, a black hole inside them that can't be filled. One reason for this is that they both lack an identity; a sense of self.

Imagine yourself an amnesia patient, adrift. Sense the paralyzing emptiness that must go with it. Know that you couldn't go too long without some kind of strategy to deal with it. People with BPD and NPD respond by using different kinds of "pain management" behaviors, which we'll talk about later. But they also have specific—and different—approaches for dealing with their identity crisis.

People with BPD become human chameleons, changing their preferences, values—even accents depending upon whom they're with. Narcissists, on the other hand, develop what's called a "false self," that superior, entitled figure we've been talking about, to mask not only the emptiness, but all kinds of painful feelings. NPs are so good at this unconscious process that they believe all the lies they tell themselves about who they are.

In this blog post, we'll take a look at the borderline strategy. In the next, I'll cover the NPD perspective.

We all act differently depending upon whom we are with: We're one person with our parents, another with our coworkers (especially the boss) and yet another with our significant other. But with BPD—as it is with every other trait—the question is the intensity of the experience and how much it negatively impacts the person's life. We may show different sides of ourselves, but we still know who we are underneath it all. People with BPD don't.

This is a trait that most of us find hard to identify with because it's so different from our own experience. Perhaps the best way to describe it is to listen to someone with BPD:

Patricia: I have a hard time figuring out who I am. I act like whomever I'm with. I've had 14 jobs since I graduated from college 10 years ago, and every time I take a career test it comes out differently. I can't decide what religion I want to be, I called around to some churches and asked them to send me some information. When I'm faced with kinds of choices—from who to have sex with to whether or not to cheat on my taxes—I don't know what to do—especially when I'm stressed or drinking. I go from one extreme to the other.

Mary: The terror of being alone and the devastation of being abandoned strike so deeply at the core of who I see myself to be that to lose a significant other is to lose myself. A borderline?s sense of identity is so shaky that we rely on someone else (our mate, our kids) to define our ego. If I cry out, "But I'll kill myself if you leave," it doesn't necessarily mean that I would entertain that notion. It does mean that I might as well be dead because I have no life other than that which is defined by being with you.

Jeff: The problem is that we people with BPD have nothing to call our own in this world, so we must rely on others to feel like we have sustenance. If a boat was an identity, then all we have is a little inflatable mattress in the middle of a huge ocean, where the waves get very big at times and sharks are all around. To survive, we must have a bigger boat. Rather than find or make our own, we hop on someone else's boat. The non-PD partner thinks they are helping a person with a small boat and it never occurs to them that the BP has no boat of their own.

Here's how this lack of identity plays itself out in relationships, with comments for non-PD partners.

Partners may pick up unwanted traits from others: She is dissatisfied with many aspects of her looks—personality, ability, intelligence—even though she is a remarkably beautiful and intelligent girl. She picks up others habits, accents, spiritual, religious beliefs at a quick pace just to be "normal." A very good example is her lie telling. Prior to September of last year she just did not lie. When she decided that everyone lies and it is normal, she started lying at a frenzied rate. She does not have the ability to differentiate a white lie from a doozy.

It contributes to no-win situations, blame and criticism: He may make an issue over something today, then tomorrow he won't care at all about that same matter. For example, one day he is friends with a person who is homosexual and so he is very concerned about the rights of homosexuals and was very critical of me for not being actively concerned with this issue. He berated me for not taking a stand and for not agreeing with hisanger at the injustice done to homosexuals. A while later, when his friendship with the homosexual person has ended, he will have no sympathy for homosexuals, and will speak disparagingly of some public figure accused of being homosexual. He will have no memory of his former views.

It's hard to have a relationship with someone who is constantly changing. Before we met, when she dated a cowboy, she dressed like a cowgirl. When she dated a Hispanic man, she spoke with an accent, to the point where people believe she's mocking them. She also does this with people's mannerisms, expressions, and other speech patterns.

What self-image they have is often low and dependent on the roles they play or whether or not they feel liked or loved at any moment in time. This is especially true with conventional (self-harming, low-functioning) BPs. After I got divorced and got primary custody of the kids, she fell into a total depression and said if she wasn't a full time mother than who was she, and what was she worth?

August 2008

The present study aims to clarify the 7th DSM-IV criterion for Borderline Personality Disorder: "chronic feelings of emptiness." Emptiness has been the subject of little empirical investigation. The relationship of emptiness to boredom and other affect-states is uncertain, and patients and clinicians can find it difficult to generate verbal descriptions of emptiness. In the present study, two sets of analyses address the meaning and clinical implications of feeling empty. First, affect-states that co-occur with emptiness are identified in 45 young adults who exhibit a prominent feature of Borderline Personality Disorder (i.e., self-injury). Second, the relationship of chronic emptiness to key psychiatric variables is examined in a large nonclinical sample (n = 274). Results indicate thatemptiness is negligibly related to boredom, is closely related to feeling hopeless, lonely, and isolated, and is a robust predictor of depression and suicidal ideation (but not anxiety or suicide attempts). Findings are consistent with DSM-IV revisions regarding the 7th criterion for Borderline Personality Disorder. In addition, findings suggest that emptiness reflects pathologically low positive affect and significant psychiatric distress.

.................................

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (1993)

by Marsha Linehan

A tendency of borderline patients to inhibit, or attempt to inhibit, emotional responses may also contribute to an absence of a strong sense of identity. The numbness associated with inhibited affect is often experienced as emptiness, further contributing to an inadequate (at at times completely absent) sense of self. Similarly, if an individual's own sense of events is never "correct" or is unpredictably "correct" -- the situation in the invalidating family -- then one would expect the individual to develop an overdependence upon others. This overdependence, especially when the dependence relates to preferences, ideas, and opinions, simply exacerbates problems with identity, and a vicious cycle is once again started.

.................................

Cascades of Emotion: The Emergence of Borderline Personality Disorder from Emotional and Behavioral Dysregulation

September 2009

...Problems with identity may lead to maladaptive cognitions, negative views of others, or feelings of emptiness. Wilkinson-Ryan and Westen (2000) have found that two specific factors of identity disturbance, painful incoherence (feelings of distress about lacking a coherent sense of self), and lack of commitment (difficulties committing to goals or maintaining a constant set of values) are highly related to the emotion dysregulation features of BPD. So identity disturbance phenomena may be part of what contributes to emotional cascades in BPD, but more research is needed to determine why this may be and if there is a relationship between identity diffusion and rumination...

.................................

Borderline Emptiness

by Randi Kreger, co-author of Stop Walking on Eggshells

October 2011

For people with BPD, feelings of emptiness go hand-in-hand with another BPD trait, lack of identity. Not knowing who you are naturally exacerbates feelings of emptiness. Those with the disorder become chameleons, mimicking some of the attributes of people they're with to fit in. We will look at this trait in some depth later on.

Also, those with BPD usually seek emotionally intimate connections--even if it means negative emotions--to help fill this chronic feeling of emptiness. When things are calm--even in a secure relationship--they may feel empty and insecure inside, so they create a conflict in order to feel more emotional intensity and connection (although this often serves to push people away, which is the opposite of their intent).

But this emptiness keeps popping up inside, driving them to seek intimacy even from people who aren't capable of it. Some professionals believe that "cutting" behavior is associated with those with BPD trying to feel "something" in order to not feel empty, disconnected, alone and abandoned.

.................................

Who Am I? The Conundrum of Both Borderlines and Narcissists

by Randi Kreger, co-author of Stop Walking on Eggshells

November 2011

In a previous post, I explained that people borderline personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder both have an awful sense of emptiness, a black hole inside them that can't be filled. One reason for this is that they both lack an identity; a sense of self.

Imagine yourself an amnesia patient, adrift. Sense the paralyzing emptiness that must go with it. Know that you couldn't go too long without some kind of strategy to deal with it. People with BPD and NPD respond by using different kinds of "pain management" behaviors, which we'll talk about later. But they also have specific—and different—approaches for dealing with their identity crisis.

People with BPD become human chameleons, changing their preferences, values—even accents depending upon whom they're with. Narcissists, on the other hand, develop what's called a "false self," that superior, entitled figure we've been talking about, to mask not only the emptiness, but all kinds of painful feelings. NPs are so good at this unconscious process that they believe all the lies they tell themselves about who they are.

In this blog post, we'll take a look at the borderline strategy. In the next, I'll cover the NPD perspective.

We all act differently depending upon whom we are with: We're one person with our parents, another with our coworkers (especially the boss) and yet another with our significant other. But with BPD—as it is with every other trait—the question is the intensity of the experience and how much it negatively impacts the person's life. We may show different sides of ourselves, but we still know who we are underneath it all. People with BPD don't.

This is a trait that most of us find hard to identify with because it's so different from our own experience. Perhaps the best way to describe it is to listen to someone with BPD:

Patricia: I have a hard time figuring out who I am. I act like whomever I'm with. I've had 14 jobs since I graduated from college 10 years ago, and every time I take a career test it comes out differently. I can't decide what religion I want to be, I called around to some churches and asked them to send me some information. When I'm faced with kinds of choices—from who to have sex with to whether or not to cheat on my taxes—I don't know what to do—especially when I'm stressed or drinking. I go from one extreme to the other.

Mary: The terror of being alone and the devastation of being abandoned strike so deeply at the core of who I see myself to be that to lose a significant other is to lose myself. A borderline?s sense of identity is so shaky that we rely on someone else (our mate, our kids) to define our ego. If I cry out, "But I'll kill myself if you leave," it doesn't necessarily mean that I would entertain that notion. It does mean that I might as well be dead because I have no life other than that which is defined by being with you.

Jeff: The problem is that we people with BPD have nothing to call our own in this world, so we must rely on others to feel like we have sustenance. If a boat was an identity, then all we have is a little inflatable mattress in the middle of a huge ocean, where the waves get very big at times and sharks are all around. To survive, we must have a bigger boat. Rather than find or make our own, we hop on someone else's boat. The non-PD partner thinks they are helping a person with a small boat and it never occurs to them that the BP has no boat of their own.

Partners may pick up unwanted traits from others: She is dissatisfied with many aspects of her looks—personality, ability, intelligence—even though she is a remarkably beautiful and intelligent girl. She picks up others habits, accents, spiritual, religious beliefs at a quick pace just to be "normal." A very good example is her lie telling. Prior to September of last year she just did not lie. When she decided that everyone lies and it is normal, she started lying at a frenzied rate. She does not have the ability to differentiate a white lie from a doozy.

It contributes to no-win situations, blame and criticism: He may make an issue over something today, then tomorrow he won't care at all about that same matter. For example, one day he is friends with a person who is homosexual and so he is very concerned about the rights of homosexuals and was very critical of me for not being actively concerned with this issue. He berated me for not taking a stand and for not agreeing with hisanger at the injustice done to homosexuals. A while later, when his friendship with the homosexual person has ended, he will have no sympathy for homosexuals, and will speak disparagingly of some public figure accused of being homosexual. He will have no memory of his former views.

It's hard to have a relationship with someone who is constantly changing. Before we met, when she dated a cowboy, she dressed like a cowgirl. When she dated a Hispanic man, she spoke with an accent, to the point where people believe she's mocking them. She also does this with people's mannerisms, expressions, and other speech patterns.

What self-image they have is often low and dependent on the roles they play or whether or not they feel liked or loved at any moment in time. This is especially true with conventional (self-harming, low-functioning) BPs. After I got divorced and got primary custody of the kids, she fell into a total depression and said if she wasn't a full time mother than who was she, and what was she worth?