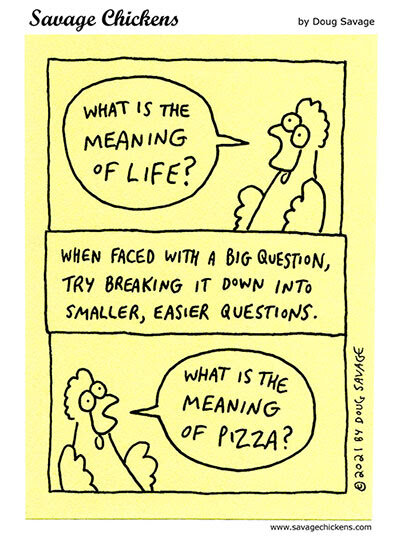

Persons high in perfectionistic concerns not only tend to catastrophize their life experiences but also struggle to accept their life experiences and to negotiate a sense of purpose, direction, and coherence in their lives. With both a catastrophic view of their present and a dark view of their past, this investigation also suggests persons high in perfectionistic concerns are at risk for depressive symptoms.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

More threads by Daniel E.

www.healthline.com

www.healthline.com

Feeling trapped in a search for deeper meaning, unable to move forward from the point of crisis, can prompt what Polish psychologist Kazimierz Dabrowski described as a “disintegration” of the self...

Along this line of thinking, existential depression can eventually lead to what Dabrowski termed reintegration. This involves a new level of deeper understanding, self-awareness, and self-acceptance.

The path to reintegration generally involves reconciling yourself to existential questions and distress and learning to manage these feelings through choices that add meaning to your life, such as living out personal values.

journals.sagepub.com

journals.sagepub.com

In people’s imagination, dying seems dreadful; however, these perceptions may not reflect reality...

Death is inevitable, but dread is not. These two studies reveal that the experience of dying is unexpectedly positive...

The common thread in the literature of the existentialists is coping with the emotional anguish arising from our confrontation with nothingness, and they expended great energy responding to the question of whether surviving it was possible. Their answer was a qualified "Yes," advocating a formula of passionate commitment and impassive stoicism.

— Alan Pratt

www.refinery29.com

www.refinery29.com

Accepting the things we cannot control is a necessary part of overcoming most manifestations of OCD. As death acceptance becomes less alternative, it’s my hope that we can all learn to talk openly about the inevitable end we all face and my belief that a culture of honesty might have helped me as an obsessive compulsive child.

...What does make life worth living? The poet Byron wrote ‘The great object of life is sensation, to feel that we exist even though in pain’ [28, p. 28]. I suggested earlier that, in the course of history, suicide might have been countered by some newly evolved appetite for staying alive. Humans collectively might have come up with some knock-down philosophical argument to chase away Santayana's scepticism. Maybe so, though we have yet to see it. But how much more promising, at the level of the individual, if natural selection acting on human genes could have found an answer internal to the self. Could mere—mere?—sensory consciousness have been refashioned in the course of human evolution just so as to make people pause before they seek oblivion?

‘There's night and day, brother, both sweet things; sun, moon, and stars, brother, all sweet things; there’s likewise the wind on the heath.’ The words are from Lavengro, the autobiographical novel of the Victorian adventurer George Borrow. As Borrow tells it, he has been reading Goethe. He's toying with the idea of suicide. He gets into conversation with a Romany gypsy, Jasper, whom he has befriended on his travels. ‘What is your opinion of death?’ says Borrow, as he sits down beside him. ‘Life is sweet, brother, who would wish to die?’ ‘I would wish to die’, says Borrow. ‘You talk like a fool’, says Jasper. ‘Wish to die indeed! There's the wind on the heath, brother; if I could only feel that, I would gladly live for ever’ [29, p. 180].

It strikes a deeply human chord. We get it. But stop to consider just how unexpected this is. How come these sweet things—‘the sun, moon and stars', ‘the wind on the heath’—can be reasons not to kill ourselves? How come we humans are so awestruck by sensory experience [30]?

The phenomenal quality of consciousness is widely regarded as a mystery. I've argued in my book Soul dust [31] that its very mysteriousness is an adaptive feature. The seemingly magical qualities of sensation—the redness of red, the saltiness of salt and the paininess of pain—have been specifically designed by natural selection to impress us with their inexplicable out-of-the-world properties. Human consciousness on this level exists as a biological adaptation precisely to ‘change the value we place on our own existence’ [32].

I've been taken to task by critics for suggesting that any biologically evolved organism could need a reason to live over and above the imperatives of life itself. But human beings are not any organism. They are the first to have had to wonder whether it's all worthwhile. We've seen in this paper the dark side. If there's a bright side, it may be that humans have come to live—perforce—in a strikingly beautiful world.

www.karger.com

www.karger.com

Existential Depression: Symptoms, in Gifted People, and Coping

Ever find yourself questioning your purpose in life or dwelling on the weight of the world? You might be dealing with existential depression.

Feeling trapped in a search for deeper meaning, unable to move forward from the point of crisis, can prompt what Polish psychologist Kazimierz Dabrowski described as a “disintegration” of the self...

Along this line of thinking, existential depression can eventually lead to what Dabrowski termed reintegration. This involves a new level of deeper understanding, self-awareness, and self-acceptance.

The path to reintegration generally involves reconciling yourself to existential questions and distress and learning to manage these feelings through choices that add meaning to your life, such as living out personal values.

Steven Hayes is good at articulating the problem here:

When Life Seems Pointless

When difficult thoughts take over, it's easy to get stuck. Here's how to escape your mental prison and turn toward meaning.www.psychologytoday.com

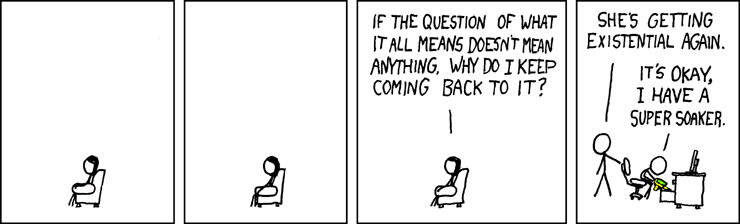

When we glimpse thoughts of meaninglessness and run from them, we give them extraordinary power over our lives. In effect, our own avoidant actions define thoughts of meaninglessness as important in the first place. Our own avoidance has transformed a thought into a thing that can run or even ruin our lives.

Last edited:

SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class research journals

Subscription and open access journals from SAGE Publishing, the world's leading independent academic publisher.

In people’s imagination, dying seems dreadful; however, these perceptions may not reflect reality...

Death is inevitable, but dread is not. These two studies reveal that the experience of dying is unexpectedly positive...

Last edited:

The Buddha always told his disciples not to waste their time and energy in metaphysical speculation. Whenever he was asked a metaphysical question, he remained silent. Instead, he directed his disciples toward practical efforts. Questioned one day about the problem of the infinity of the world, the Buddha said, "Whether the world is finite or infinite, limited or unlimited, the problem of your liberation remains the same." Another time he said, "Suppose a man is struck by a poisoned arrow and the doctor wishes to take out the arrow immediately. Suppose the man does not want the arrow removed until he knows who shot it, his age, his parents, and why he shot it. What would happen? If he were to wait until all these questions have been answered, the man might die first." Life is so short. It must not be spent in endless metaphysical speculation that does not bring us any closer to the truth.

— Thich Nhat Hanh

Last edited:

The common thread in the literature of the existentialists is coping with the emotional anguish arising from our confrontation with nothingness, and they expended great energy responding to the question of whether surviving it was possible. Their answer was a qualified "Yes," advocating a formula of passionate commitment and impassive stoicism.

— Alan Pratt

Life as a bad dream:

“We can regard our life as a uselessly disturbing episode in the blissful repose of nothingness.”

~ Arthur Schopenhauer

“We can regard our life as a uselessly disturbing episode in the blissful repose of nothingness.”

~ Arthur Schopenhauer

David Baxter PhD

Late Founder

Well, that's uplifting.

At least with me, I think existential OCD is a theme that gives me a break (or secondary gain) from dealing with other OCD themes. So what is good for OCD in general is good for existential OCD. For example, regarding "fear of self" and pathological guilt:

Last edited:

How Learning About Death Helped My OCD

Sometimes OCD develops after the death of a loved one. Marianne Eloise explains how coming to terms with dying has helped her condition.

Accepting the things we cannot control is a necessary part of overcoming most manifestations of OCD. As death acceptance becomes less alternative, it’s my hope that we can all learn to talk openly about the inevitable end we all face and my belief that a culture of honesty might have helped me as an obsessive compulsive child.

Last edited:

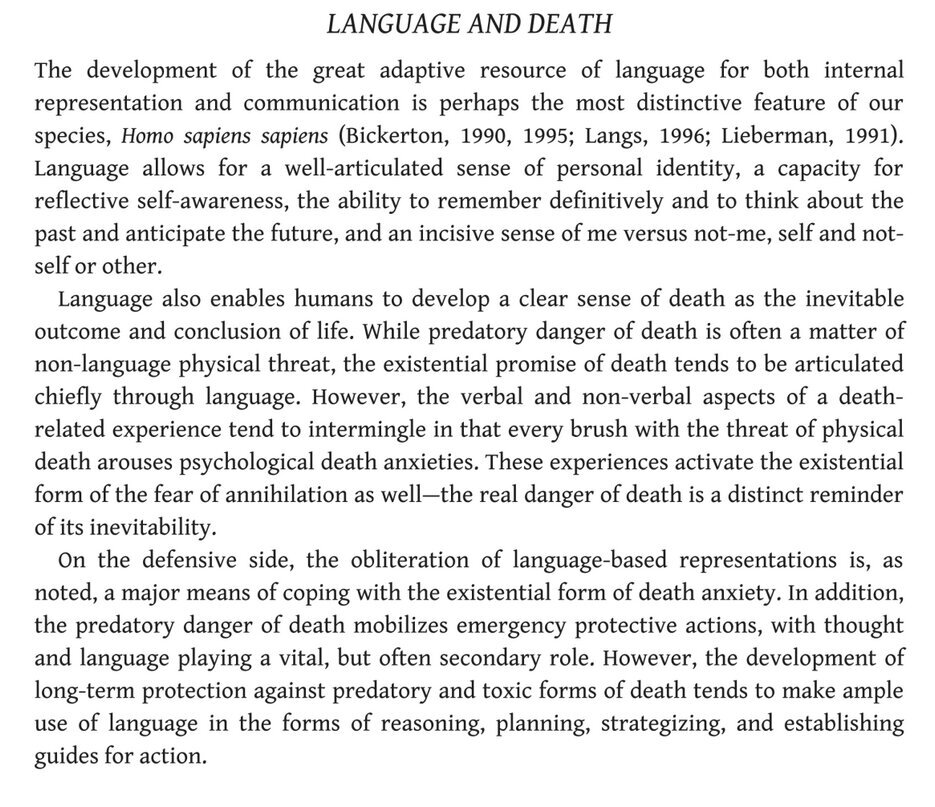

Death Anxiety and Clinical Practice

Robert Langs argues that death anxiety is neglected - in part, because of treatment failures due to countertransference interferences during treatment. He then discusses the technical issues connected with this, whilst introducing the controversial concept that mental activities are derived from...

www.google.com

“Somehow, like so many people who get depressed, we felt our depressions were more complicated and existentially based than they actually were.”

― Kay Redfield Jamison, An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness

― Kay Redfield Jamison, An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness

The lure of death: suicide and human evolution | Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

At some point in evolutionary history, human beings came to understand, as no non-human animals do, that death brings to an end a person's bodily and mental presence in the world. A potentially devastating consequence was that individuals, seeking to ...

royalsocietypublishing.org

The lure of death: suicide and human evolution

by Nicholas Humphrey...What does make life worth living? The poet Byron wrote ‘The great object of life is sensation, to feel that we exist even though in pain’ [28, p. 28]. I suggested earlier that, in the course of history, suicide might have been countered by some newly evolved appetite for staying alive. Humans collectively might have come up with some knock-down philosophical argument to chase away Santayana's scepticism. Maybe so, though we have yet to see it. But how much more promising, at the level of the individual, if natural selection acting on human genes could have found an answer internal to the self. Could mere—mere?—sensory consciousness have been refashioned in the course of human evolution just so as to make people pause before they seek oblivion?

‘There's night and day, brother, both sweet things; sun, moon, and stars, brother, all sweet things; there’s likewise the wind on the heath.’ The words are from Lavengro, the autobiographical novel of the Victorian adventurer George Borrow. As Borrow tells it, he has been reading Goethe. He's toying with the idea of suicide. He gets into conversation with a Romany gypsy, Jasper, whom he has befriended on his travels. ‘What is your opinion of death?’ says Borrow, as he sits down beside him. ‘Life is sweet, brother, who would wish to die?’ ‘I would wish to die’, says Borrow. ‘You talk like a fool’, says Jasper. ‘Wish to die indeed! There's the wind on the heath, brother; if I could only feel that, I would gladly live for ever’ [29, p. 180].

It strikes a deeply human chord. We get it. But stop to consider just how unexpected this is. How come these sweet things—‘the sun, moon and stars', ‘the wind on the heath’—can be reasons not to kill ourselves? How come we humans are so awestruck by sensory experience [30]?

The phenomenal quality of consciousness is widely regarded as a mystery. I've argued in my book Soul dust [31] that its very mysteriousness is an adaptive feature. The seemingly magical qualities of sensation—the redness of red, the saltiness of salt and the paininess of pain—have been specifically designed by natural selection to impress us with their inexplicable out-of-the-world properties. Human consciousness on this level exists as a biological adaptation precisely to ‘change the value we place on our own existence’ [32].

I've been taken to task by critics for suggesting that any biologically evolved organism could need a reason to live over and above the imperatives of life itself. But human beings are not any organism. They are the first to have had to wonder whether it's all worthwhile. We've seen in this paper the dark side. If there's a bright side, it may be that humans have come to live—perforce—in a strikingly beautiful world.

Last edited:

“Perhaps depression is caused by asking oneself too many unanswerable questions.”

― Miriam Toews, Swing Low: A Life

“Things shouldn't hinge on so very little. Sneeze and you're highway carnage. Remove one tiny stone and you're an avalanche statistic. But I guess if you can die without ever understanding how it happened then you can also live without a complete understanding of how. And in a way that's kind of relaxing.”

― Miriam Toews, A Complicated Kindness

“Doubt and uncertainty and questioning are inextricably bound together with faith.”

“Freedom is good...it's better than slavery. And forgiveness is good, better than revenge. And hope for the unknown is good, better than hatred of the familiar.”

― Miriam Toews, Women Talking

― Miriam Toews, Swing Low: A Life

“Things shouldn't hinge on so very little. Sneeze and you're highway carnage. Remove one tiny stone and you're an avalanche statistic. But I guess if you can die without ever understanding how it happened then you can also live without a complete understanding of how. And in a way that's kind of relaxing.”

― Miriam Toews, A Complicated Kindness

“Doubt and uncertainty and questioning are inextricably bound together with faith.”

“Freedom is good...it's better than slavery. And forgiveness is good, better than revenge. And hope for the unknown is good, better than hatred of the familiar.”

― Miriam Toews, Women Talking

Last edited:

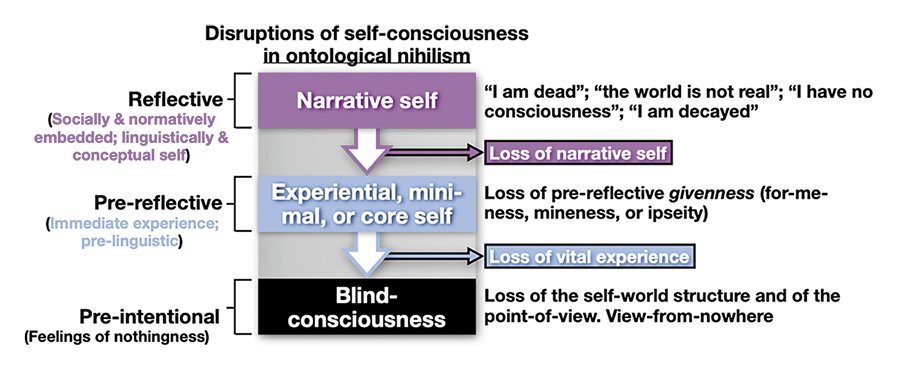

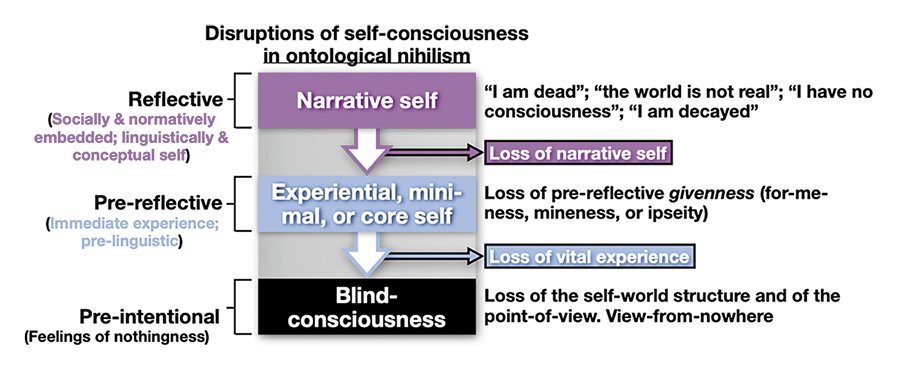

When the World Breaks Down: A 3-Stage Existential Model of Nihilism in Schizophrenia

Abstract. The existential crisis of nihilism in schizophrenia has been reported since the early days of psychiatry. Taking first-person accounts concerning nihilistic experiences of both the self and the world as vantage point, we aim to develop a dynamic existential model of the pathological...

Replying is not possible. This forum is only available as an archive.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 15K

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 6K