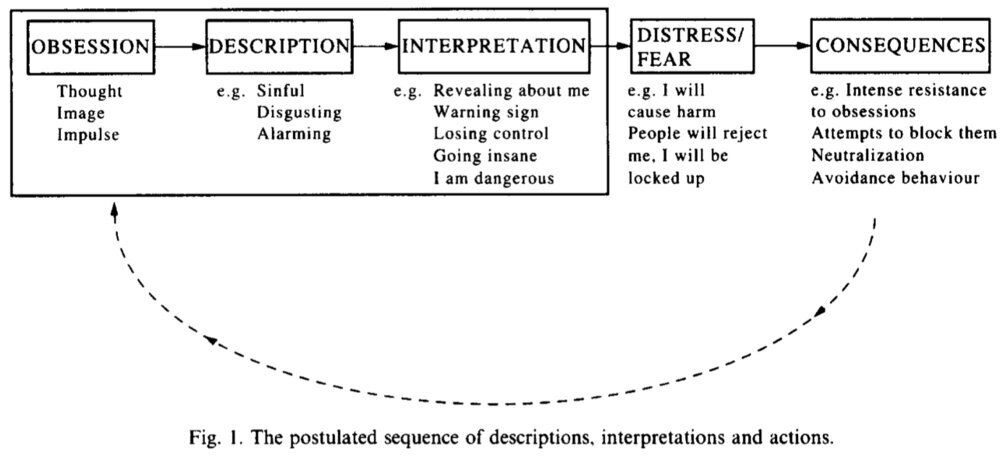

CBT (cognitive behavior therapy) involves actively challenging and confronting the distorted thinking and beliefs that drive and maintain obsessions and compulsions. Below are the key cognitive errors of people with OCD.

Black-and-White or All-or Nothing Thinking

Example: "If I’m not completely safe, then I’m in overwhelming danger."

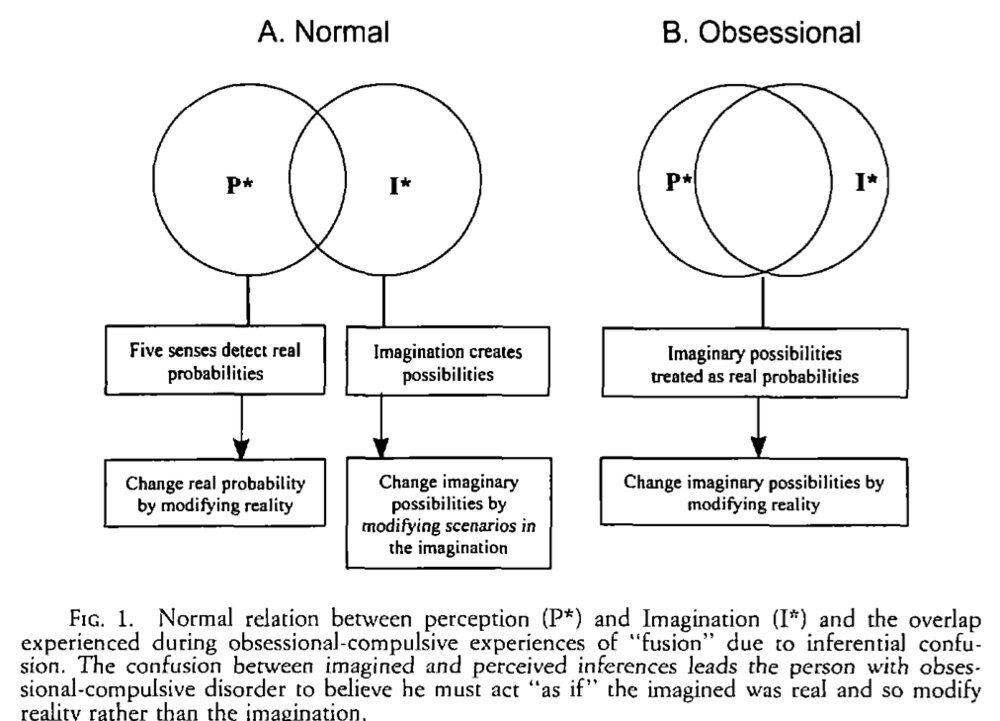

Magical Thinking

Example: "If I think bad thoughts, bad things will happen."

Overestimating Risk and Danger

Example: "If I take even a slight risk, I will come to great harm."

Perfectionism

Example: "I’ve got to do everything perfectly."

Hypermorality

Example: "I’ll be punished for every mistake."

Overresponsibility for Others

Example: "I must always guard against making mistakes that even remotely harm an innocent person."

Thought-Action Fusion (similar to Magical Thinking)

Example: "If I have a bad, even horrible thought about harming someone, it feels just as if I've actually done it or that it is highly likely to happen in the future."

Overimportance of Thought

Example: "If I think about a terrible event occurring, it is much more likely to happen."

Exclusivity Error

Example: "Bad things are much more likely to happen to me than to other people."

Martyr Complex

Example: "Suffering and sacrificing my life by doing endless rituals is a small price to pay to protect those I love. Since no harm has come to them, I must be doing something right."

“What If” Thinking

Example: "In the future, what if I...

do it wrong?"

make a mistake?"

get AIDS?"

am responsible for causing harm to someone?"

Intolerance of uncertainty

Example: "I can’t relax until I am 100% certain of everything and know everything will be OK."

Adapted from: The OCD Workbook: Your guide to breaking free from obsessive-compulsive disorder

Preview at: The OCD Workbook: Your guide to breaking free from obsessive-compulsive disorder

Black-and-White or All-or Nothing Thinking

Example: "If I’m not completely safe, then I’m in overwhelming danger."

Magical Thinking

Example: "If I think bad thoughts, bad things will happen."

Overestimating Risk and Danger

Example: "If I take even a slight risk, I will come to great harm."

Perfectionism

Example: "I’ve got to do everything perfectly."

Hypermorality

Example: "I’ll be punished for every mistake."

Overresponsibility for Others

Example: "I must always guard against making mistakes that even remotely harm an innocent person."

Thought-Action Fusion (similar to Magical Thinking)

Example: "If I have a bad, even horrible thought about harming someone, it feels just as if I've actually done it or that it is highly likely to happen in the future."

Overimportance of Thought

Example: "If I think about a terrible event occurring, it is much more likely to happen."

Exclusivity Error

Example: "Bad things are much more likely to happen to me than to other people."

Martyr Complex

Example: "Suffering and sacrificing my life by doing endless rituals is a small price to pay to protect those I love. Since no harm has come to them, I must be doing something right."

“What If” Thinking

Example: "In the future, what if I...

do it wrong?"

make a mistake?"

get AIDS?"

am responsible for causing harm to someone?"

Intolerance of uncertainty

Example: "I can’t relax until I am 100% certain of everything and know everything will be OK."

Adapted from: The OCD Workbook: Your guide to breaking free from obsessive-compulsive disorder

Preview at: The OCD Workbook: Your guide to breaking free from obsessive-compulsive disorder